Taking Stock of Denver Placemaking

Denver is earning a reputation as a city to watch for 21st century placemaking. Its Lower Downtown (LoDo) historic district—a mixed-use area now 25 years in the making—is a revitalization success story. The city is making major investments in transit-oriented development, highlighted by its FasTracks light rail system and newly refurbished Union Station. New Urbanist retrofits of the old municipal airport (Stapleton) and dead suburban shopping malls (e.g., Belmar) are much-discussed examples of how to get it right. Denver has an active Tactical Urbanism movement. Amenities to attract the coveted target population of Millennials and other cultural creatives are popping up left and right…though not always with flattering results. These efforts are propelling Denver to the top of city rankings for livability including—astonishingly enough for the sprawling “Queen City of the Plains”—walkability.

Lately there has been some stocktaking to critically evaluate Denver’s progress. Last April Confluence Denver—the city’s “online magazine for entrepreneurs and creatives”—convened local developers, planners, and architects for an open public conversation about “Place and Why it Matters.” Last May Politico Magazine visited Denver to talk about transportation with Mayor Michael Hancock as part of its national “What Works” series. I discuss both of these events, and some particular Denver placemaking projects, over at Planetizen. The story I tell is one of hits, misses, and open questions.

Among the most persistent of these open questions is what will happen at the site of the former University of Colorado Health Sciences Center (UCHSC) campus at 9th Avenue and Colorado Boulevard in east-central Denver. Only passing reference was made in the Confluence Denver discussion to this project. Jesse Adkins of Shears Adkins Rockmore Architects had this to say about the challenge of developing the former Health Sciences Center campus:

“That’s a tough one to solve…”Lots of issues and big problems. These buildings have been there for 100 years. The street grid exists. There are ingredients you can pull into it. It’s one of those nodal opportunities that could continue to fill in gaps around the city.”

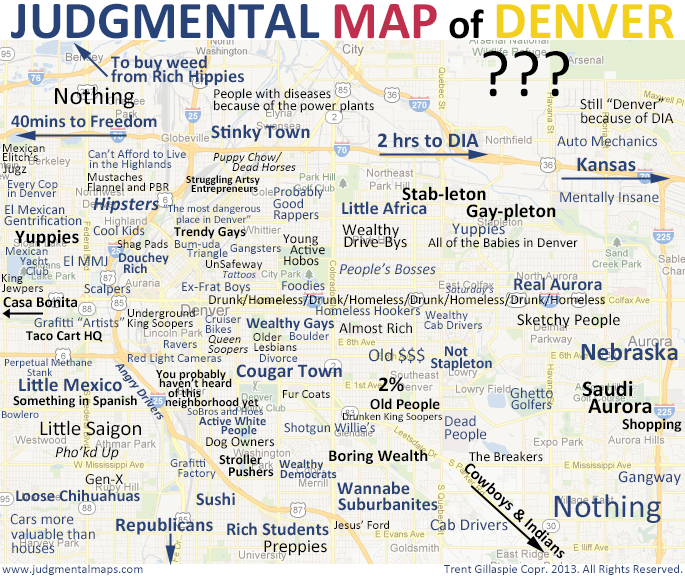

Adkins is right, especially his point about the campus site presenting a “nodal” opportunity. In fact, the site is pretty much smack dab in the middle of Trent Gillaspie’s cheeky “Judgmental Map of Denver” that, along with the Judgmental Maps of other cities, has been getting a lot of run on the internet. Although it’s not entirely evident from Gillaspie’s map the UCHSC site is located at the nexus of multiple neighborhoods that, according to the most recent census data, are sharply divided by class and culture. According to the research of Richard Florida and colleagues (see here and here), Denver ranks #9 in income segregation among large American metros. It’s running neck-and-neck with Dallas for last place among major American cities with the smallest percentage of homes available for purchase (around 15 percent) in the least expensive tier of housing. Denver’s cost of rental housing is also among the highest in the nation. Thus, the UCHSC site development offers an excellent opportunity to both socially de-segregate and spatially re-connect this portion of a fractured city. It’s positioned to address multiple citizen needs and perhaps accomplish some beneficial mixing of people and ideas. Because of this potential the UCHSC site is, for my money, the most important placemaking exercise to watch in the entire city of Denver.

I’ve been chronicling the history of the UCHSC development elsewhere on this blog. Unsurprisingly, this history is one of controversy and conflict because of the site’s location, a volatile economy, a steady parade of would-be developers, conflicting developer visions, and citizen disagreements about what should fill the site. In my view the biggest obstacles to development are (1) citizens from wealthier adjacent neighborhoods whose obstructionism was catalyzed by a plan to include a Walmart store in the retail mix, and (2) city councilpersons who are much too invested in serving this well-heeled demographic to the exclusion of all others. Rather unimaginative New Urbanist conceptions of architectural design also don’t help. The site begs a plan and an architecture that respects both its spatial “nodality” and its 100-year history as a hospital and medical research facility. The dearth of exciting design ideas is perplexing given that Denver has one of the highest densities of architects in the entire nation. However, there’s still cause for optimism. The latest new developer (the same developer who gave us Belmar) is looking to preserve additional historical structures and to workshop with neighborhood kids about their desires for the site. Whether this developer will build creatively, and for a diverse demographic, remains to be seen.

A story published just today at Confluence Denver notes that placemaking in the city has been about taking “incremental steps”, the big projects like Union Station notwithstanding. Downtown Denver Partnership president and CEO Tammy Door says that the city has been “bunting” with small projects year after year in addition to hitting the occasional “home run.” I’d add that other forms of “small ball” (to stay with the baseball metaphors) like short-term public art and architecture projects, among other tactical urbanist interventions, have also been important for illustrating what’s possible in Denver placemaking. But such interventions can never address the most compelling structural issues around urban social and spatial inequality that affect American cities. Thinking inclusively has to extend beyond the Millennials and cultural creatives that Denver, like many other cities, is going out of its way to attract. We need to harness urban diversity in all of its forms, and embrace residents both old and new, in order to make good places and thereby realize the city’s “diversity advantage.” Civic Leadership at multiple levels is crucial to achieving this goal.

This essay was re-posted to Sustainable Cities Collective.

Leave a Reply