Will the Development at 9th and Colorado be Kid-Friendly?

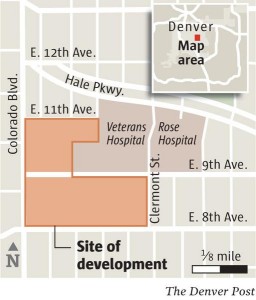

The Colorado Boulevard Healthcare District Board was scheduled to meet last week to receive an update from the 9th and Colorado developer and architect, but when I showed up at the designated place no one was there except another confused would-be attendee. Apparently we both missed the memo cancelling or moving the meeting. However, The Denver Post ran a story about the planned development on Wednesday the 17th that basically reports what we posted here last month. Accompanying the story is the following conceptual rendering of the project’s Bellaire Street entry:

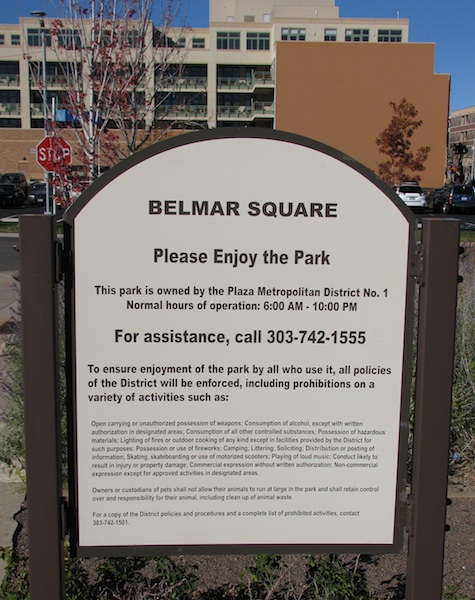

Three Post readers commented on the article. One was hoping, obviously tongue-in-cheek, for a “big roller coaster and water slides through the old hospital”, but then offered a more sober hope that a place will be created “for teens to gather and have fun.” Another reader speculated that the development will “reflect new urbanism and be slick and sophisticated.” That’s probably a sure bet, in which case teens and other young folk might be out of luck. Although New Urbanism prides itself on family-friendliness—witness the many parks, playing fields, and outdoor amenities at the Stapleton development in Denver—there’s no guarantee that this will happen. The New Urban retrofit at Belmar in Lakewood (a Denver suburb), for example, caters to young urban professionals and adult consumers. The Belmar Plaza is intentionally designed to be skateboard unfriendly (although there was nothing that would have precluded constructing something for kids adjacent to, and inter-visible with, the plaza), and the sign detailing the limits on use of the Belmar Square clearly signals that this is closely monitored and regulated space.

Ninth and Colorado is certainly small as infill projects go and it obviously can’t cater to every need. But two important people—City Councilwoman Jeanne Robb and Mary Nell Wolff, Chairwoman of the CBHD Board—have expressed desires that the development will “blend into the neighborhood” (Robb) and “allow the neighborhoods and the property to work together again” (Wolff). If that sentiment is shared by the developer, architect, and merchants then thought should be given to kids. Kids haven’t yet appeared in any of the project’s conceptual renderings, including the one above. Bringing them into the picture and the conversation would also be in keeping with a vision of the Inclusive City.

There’s a small literature dealing with kids and urban design that can inform infill development that’s sensitive to the youth demographic of surrounding neighborhoods. Much of the current work plays off of Enrique Peñalosa‘s idea that all urban planning should start with children; that they are an “indicator species” for evaluating the livability of a city. Peñalosa is the former mayor of Bogota who initiated, among other things, the ciclovías described in our last post. Extending Peñalosa’s argument, Lisa Weston specifies that the target audience or “prototypical citizen” for building cities is 11-15 year olds. The rationale is as follows. Environmental psychologists and neuropsychiatrists suggest that the human brain is developing its spatial knowledge and competencies between 11-15 years of age. This is also the age at which kids are independent enough to interact with the urban environment in ways that hone these skills and competencies. To maximize such interaction kids must have greater freedom to navigate urban space. A city that challenges and incentivizes kids to develop their spatial competencies by moving around also addresses America’s child obesity problem and the reality that kids made overweight by a sedentary existence usually become overweight adults. Where kids are free to move and learn they also gain in self-esteem, which can improve their social interaction skills.

As noted above, New Urbanism very often produces built environments that encourage the development of spatial competency by virtue of its emphasis on compact, dense, walkable, and mixed use communities allowing easy access to a variety of public amenities like parks and playgrounds. Variety should also characterize neighborhood architecture. This is arguably a more elusive goal given that New Urbanism tends to trade in a very traditional, small town America architectural style that, though appealing to a large chunk of the American middle-class, is for many critics becoming far too commonplace on the American landscape. If identifying and naming landmarks is important for cultivating powers of spatial thinking (as Weston seems to suggest), then architectural diversity beyond that offered up by the New Urbanism might better serve the cause of childhood cognitive development.

Many other aspects of the built environment can also serve this cause. Researchers say that apartment houses no taller than four stories incentivize a child’s interaction with their friends. Any greater distance between floors or between floor and street gives kids excuses to stay inside and play video games. Rooftop play areas and the kinds of qualities that would be at home in Latino Urbanism—courtyards, shared backyards, and wide sidewalks—further benefit cognitive and social development. Interactive pieces of public art and water features are always huge attractors for kids. Multifunctional street furniture like gazebos accommodate sitting and a variety of other activities that allow self and small group expression. Failing that, there are always bushwaffles…

Finally, a pedestrian bridge over Colorado at 9th Avenue–if not precluded by the General Development Plan or some other legal or logistical obstacle–would neatly thread the new infill development into the adjacent Congress Park neighborhood and, indeed, offer a straight shot westward into the eponymous park via the connecting 9th Avenue. This one feature alone would greatly expand the size of the urban environment through which children of appropriate age can independently move and learn.

Finally, a pedestrian bridge over Colorado at 9th Avenue–if not precluded by the General Development Plan or some other legal or logistical obstacle–would neatly thread the new infill development into the adjacent Congress Park neighborhood and, indeed, offer a straight shot westward into the eponymous park via the connecting 9th Avenue. This one feature alone would greatly expand the size of the urban environment through which children of appropriate age can independently move and learn.

Leave a Reply