Three Urbanisms Revisited

A recurring theme in the urban studies literature and blogosphere (including this blog) is critical comparison of different approaches to city-building. Such an exercise can have practical utility in the street and also pedagogical utility in the classroom. Although any typology of urbanisms is inevitably reductive (but see here for a particularly informative and engaging perspective), typologizing can help clarify distinguishing features and emphases, points at which alternative approaches converge, and viewpoint differences that are irreconcilable.

With that in mind, I want to examine Douglas Kelbaugh’s comparison of the three paradigms of New Urbanism, Everyday Urbanism, and Post Urbanism. In at least four essays over the last 10 years (e.g., here and here) Kelbaugh has usefully compared the values and outcomes of each, along with what he sees as their respective merits and liabilities. He has also identified the one that he believes offers the best framework for improving the American city.

Denver’s New Urban Stapleton Community (from Kelbaugh’s “Toward an Integrated Paradigm: Further Thoughts on the Three Urbanisms”, courtesy of Calthorpe Associates)

Three Urbanisms

New Urbanism is the most well-known and widely practiced of the three urbanisms. Its commitment to designing compact, mixed-use, transit-friendly, and walkable cities overlaps with that of many competitors. However, New Urbanism strives more than most to cultivate community in urban design via investments in public space. It is also distinctive in emphasizing a very particular neo-traditional or “pitched roof and front porch” aesthetic that has proven its appeal to a broad swath of the American population.

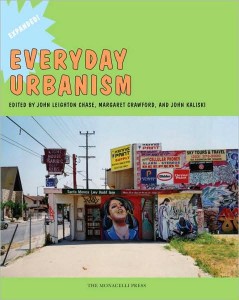

Everyday Urbanism eschews a unifying urban plan and aesthetic. It is more cognizant than most of the manifold cultural differences that citizens bring to urban place-making. It is keen to let differences in space use and built form proliferate in keeping with these cultural backgrounds and interests. It celebrates spontaneity in place-making and, famously, the design elements of “ephemerality, cacophony, multiplicity, and simultaneity.”

Post Urbanism is Kelbaugh’s term for the work of urban designers and architects like Koolhaas, Libeskind, Hadid, Gehry, and others. Like Everyday Urbanism, Post Urbanism rejects formal design orthodoxies and principles. However, there’s a shared commitment to experiment with new designs that make bold, dramatic statements within the urban fabric. These forms occupy a continuum from broken, fractal designs to sweeping arcs and curves. In contrast to New Urbanism’s traditional forms and Everyday Urbanism’s vernacular forms, Post Urbanism’s forms are sensational, and clearly designed to “wow.”

Evaluation

Kelbaugh is admirably even-handed in identifying the pros and cons of these paradigms. He likes the aesthetic unity of New Urbanism but worries about its normativity; i.e., the way it romanticizes a particular past. He appreciates the populism of Everyday Urbanism but is troubled by the absence of a larger, unifying design aesthetic. Everyday Urbanism risks place-making “by default rather than by design.” Like most of us Kelbaugh is excited by Post Urbanism’s experimentalism (it eyes the future while New Urbanism mythologizes the past and Everyday Urbanism privileges the prosaic present), but worries about its tendency to produce buildings that out-scale humans and disconnect from their surroundings.

At same time Kelbaugh recognizes that each urbanism can have its virtues depending on urban context. He suggests that Everyday Urbanism is the best choice for squatter cities of the Global South where immigrants and refugees struggle to create for themselves an urban identity and niche. On the other hand, Post Urbanism is the best choice for European cities where a radically new building can offer welcome relief in a mature, high density urban fabric. New Urbanism offers the best hope for the “typical” American city that lacks density but has the economic capacity to achieve coherence. It represents a “middle road” that’s less glamorous than Post Urbanism but more ambitious than Everyday Urbanism.

Urban Epistemologies

While Kelbaugh’s typology could be updated and/or expanded to take stock of some recent entries into Urbanism’s battle for hearts and minds—e.g., Waldheim’s Landscape Urbanism or its close kin, Mostafavi’s Ecological Urbanism—it remains a useful way to grasp how different approaches deal with a number of urban design variables. One analytical dimension that Kelbaugh does not fully pursue is implicated by his use of term paradigm to describe these different approaches to urbanism. This dimension is the epistemological one—the understanding of professional design knowledge that underpins each approach.

New Urbanism can be described as broadly idealist, to the extent that it is informed by a codified set of ideals and principles about what urbanism should look like in order to best serve the interests of human community. New Urbanists are confident about the ability of their principles to produce the good city. They also trust that alternative approaches are commensurable and that different ideas can be assimilated into a single, coherent vision of urbanism (i.e., their’s). Post Urbanism is broadly relativist, dedicated to exploring brand new forms of architectural and design knowledge. The attitude is “anything goes,” which is perhaps most apparent in those forms that have been widely criticized for out-scaling humans and disconnecting from the street. Finally, Everyday Urbanism is broadly pragmatist. It respects different, culturally-specific ideas about city-building and arguably is more concerned than the others about the consequences of design acts for everyday life, for how people live. I think Kelbaugh hints at these epistemological orientations where, in this particular piece, he suggests that New Urbanists see themselves as urban design “experts”, Post Urbanists fancy themselves as “lone geniuses”, and Everyday Urbanists engage with community members as “co-participants” in the design conversation.

In Defense of Everyday—and Intercultural—Urbanism

Viewed from this perspective, I think that the contemporary American city is best served not by New Urbanism, but rather by Everyday Urbanism. Contributors to Everyday Urbanism, especially John Kaliski, explain why. In so doing I think they also neatly articulate a pragmatist epistemology and ethos. For Everyday Urbanism—as for Intercultural Urbanism—the “primary element” and “most salient fact” of everyday urban life is difference. Not only ethnic difference but also class difference. Andres Duany admits that New Urbanism seeks to connect to the American middle class, and Douglas Kelbaugh admits that Post Urbanism succeeds best where you have a wealthy, sophisticated consumer citizenry to support it. Certainly American cities are becoming increasingly diverse in terms of ethnic and class make-up. Some are even taking on “squatter settlement” characteristics as America’s homeless problem deepens. It’s thus becoming increasingly important to design or “script” spaces in ways that serve diverse urban cultures, including their histories and memories. Interestingly, advocates of Ecological Urbanism are also aware of this reality and its design challenge. Meeting the challenge of designing for diversity must include the scripting of spaces that can accommodate spontaneity, unpredictability, new opportunities, and unforeseen possibilities. Although Everyday Urbanism is reluctant to articulate a particular design aesthetic, planners and designers don’t disappear. Rather, they enable conversation with stakeholders, work to achieve consensus through what pragmatists call “unforced agreement”, and help co-author the urban script. The epistemological test of an Everyday or Intercultural Urbanist script is not whether it reaches new levels of “wow” or can neatly assimilate the best ideas of alternative urbanisms, but whether it succeeds in weaving together cultural differences in place-making.

Viewed from this perspective, I think that the contemporary American city is best served not by New Urbanism, but rather by Everyday Urbanism. Contributors to Everyday Urbanism, especially John Kaliski, explain why. In so doing I think they also neatly articulate a pragmatist epistemology and ethos. For Everyday Urbanism—as for Intercultural Urbanism—the “primary element” and “most salient fact” of everyday urban life is difference. Not only ethnic difference but also class difference. Andres Duany admits that New Urbanism seeks to connect to the American middle class, and Douglas Kelbaugh admits that Post Urbanism succeeds best where you have a wealthy, sophisticated consumer citizenry to support it. Certainly American cities are becoming increasingly diverse in terms of ethnic and class make-up. Some are even taking on “squatter settlement” characteristics as America’s homeless problem deepens. It’s thus becoming increasingly important to design or “script” spaces in ways that serve diverse urban cultures, including their histories and memories. Interestingly, advocates of Ecological Urbanism are also aware of this reality and its design challenge. Meeting the challenge of designing for diversity must include the scripting of spaces that can accommodate spontaneity, unpredictability, new opportunities, and unforeseen possibilities. Although Everyday Urbanism is reluctant to articulate a particular design aesthetic, planners and designers don’t disappear. Rather, they enable conversation with stakeholders, work to achieve consensus through what pragmatists call “unforced agreement”, and help co-author the urban script. The epistemological test of an Everyday or Intercultural Urbanist script is not whether it reaches new levels of “wow” or can neatly assimilate the best ideas of alternative urbanisms, but whether it succeeds in weaving together cultural differences in place-making.

Sensibility vs. Hegemony in Urban Design

In his concluding chapter to Everyday Urbanism John Kaliski addresses Kelbaugh’s “design by default” criticism by defending Everyday Urbanism as a paradigmatic “middle ground” that’s “truer” than the one that Kelbaugh claims for New Urbanism. I don’t think we need to go there. Middle ground-ism is as potentially hegemonic as singular vision-ism, middle road-ism, or synthetic alternatives such as cityism. Interestingly, both Kaliski and Kelbaugh suggest that urbanism, at its deepest level, rests on a particular set of sensibilities. So too does Mostafavi. The future of the American city is best served by debating the substance and consequences of these sensibilities, not paradigmatic hegemony.

One Comment

Leave a Reply