Brand X Urbanism and Cultural Diversity

I’d like to revisit an issue raised in my recent summary of James Kunstler’s view of the urban future. This issue is the relative merits of competing urbanisms for addressing the contemporary challenges that confront city designers and planners. Kunstler identifies New Urbanism as the only urbanism capable of informing design choices for the future, and suggests that many urbanisms on the ever-expanding list of “Brand X” (or, “Fill in the Blank“) alternatives —he specifically mentions Landscape Urbanism—are “fashion statements” that offer little additional value.

The often acrimonious debate between New and Landscape (or, alternatively, Ecological) Urbanists is certainly the showdown that’s generated the most recent heat (e.g., see here and, for an exemplary piece of side-taking, here). I tend to agree with those observers who argue that, given the magnitude of the urban challenges facing us, we should be open to any conceptual suggestion for re-making cities regardless of its source (e.g., see here and here and various commentators here). From an anthropological perspective it only makes sense that any plan, Big or Little, should harmonize with the natural environment and employ architecture as a strategy for nurturing commitments to place. Thus, interventions in the New Urbanism-Landscape Urbanism debate that call for a better and less divisive conversation aimed at forging some consensus if not a holistic, hybrid, or “planetary” urbanism are well-taken.

The often acrimonious debate between New and Landscape (or, alternatively, Ecological) Urbanists is certainly the showdown that’s generated the most recent heat (e.g., see here and, for an exemplary piece of side-taking, here). I tend to agree with those observers who argue that, given the magnitude of the urban challenges facing us, we should be open to any conceptual suggestion for re-making cities regardless of its source (e.g., see here and here and various commentators here). From an anthropological perspective it only makes sense that any plan, Big or Little, should harmonize with the natural environment and employ architecture as a strategy for nurturing commitments to place. Thus, interventions in the New Urbanism-Landscape Urbanism debate that call for a better and less divisive conversation aimed at forging some consensus if not a holistic, hybrid, or “planetary” urbanism are well-taken.

But even these synthetic efforts are likely to be limited without more thoroughgoing attention to the difference that culture makes in how people relate to both environment and architecture. Provocative and compelling arguments have been made that all cultural groups have tendencies to value particular kinds of landscapes as a result of a shared evolutionary history. However, urbanisms that start with the natural environment can still benefit from more research on how ethnic groups “cognize” their natural surroundings differently as a function of history and socialization (see also here).

Like Landscape Urbanism, the latest version of New Urbanism—what founder Andres Duany calls Agrarian Urbanism—can benefit from a more serious engagement with the phenomenon of culture. Agrarian Urbanism is keen to address problems of urban sustainability by incorporating various forms of food production into the basic New Urban fabric. These include, among other things, medium-sized farms (a substitute for golf course fairways) and community gardens (a substitute for front yards). But while Duany is explicit in distinguishing Agrarian Urbanism by highlighting its emphasis on food production as a societal commitment, society is not equivalent to culture. Choices around food–what is grown, how it is harvested and prepared, how and where it is consumed, its symbolic meaning, and so on–are choices central to how a culture defines itself. It is striking, for example, that in current formulations of Agrarian Urbanism cultural diversity appears only in the form of “Hispanic laborers” who will continue to be called upon to do the “dirty work” associated with the more labor-intensive forms of urban farming (albeit in the context of “a closer relationship with their employers”). As Mike Soron notes, Agrarian Urbanism risks “repurposing an economic underclass from ornamental landscaping and golf course maintenance to productive cultivation.” And, as Greg Lindsay suggests, if Agrarian Urbanism sticks with New Urbanist town planning and architectural principles this repurposing is likely to take place in a built setting strongly redolent of pre-1850s small-town–i.e., Anglo–America. In short, Agrarian Urbanism as currently formulated risks producing a “New Feudalism” driven by a particularly narrow and potentially highly exclusive set of cultural expectations and prescriptions.

Like Landscape Urbanism, the latest version of New Urbanism—what founder Andres Duany calls Agrarian Urbanism—can benefit from a more serious engagement with the phenomenon of culture. Agrarian Urbanism is keen to address problems of urban sustainability by incorporating various forms of food production into the basic New Urban fabric. These include, among other things, medium-sized farms (a substitute for golf course fairways) and community gardens (a substitute for front yards). But while Duany is explicit in distinguishing Agrarian Urbanism by highlighting its emphasis on food production as a societal commitment, society is not equivalent to culture. Choices around food–what is grown, how it is harvested and prepared, how and where it is consumed, its symbolic meaning, and so on–are choices central to how a culture defines itself. It is striking, for example, that in current formulations of Agrarian Urbanism cultural diversity appears only in the form of “Hispanic laborers” who will continue to be called upon to do the “dirty work” associated with the more labor-intensive forms of urban farming (albeit in the context of “a closer relationship with their employers”). As Mike Soron notes, Agrarian Urbanism risks “repurposing an economic underclass from ornamental landscaping and golf course maintenance to productive cultivation.” And, as Greg Lindsay suggests, if Agrarian Urbanism sticks with New Urbanist town planning and architectural principles this repurposing is likely to take place in a built setting strongly redolent of pre-1850s small-town–i.e., Anglo–America. In short, Agrarian Urbanism as currently formulated risks producing a “New Feudalism” driven by a particularly narrow and potentially highly exclusive set of cultural expectations and prescriptions.

The insensitivity to culture evident in the more higher profile competing urbanisms is why I think Latino Urbanism—to the extent that it foregrounds issues of culture—should be closely watched as one Brand X alternative that’s capable of pointing the way to a more holistic, sustainable, and democratic approach to city-making. Leading advocates of Latino Urbanism like James Rojas, Michael Mendez, Teddy Cruz, and Katherine Perez think broadly and deeply about the kinds of design elements that best serve Latino cultural values and preferences. These include preferences for high density neighborhoods connected by public transport, for a variety of housing options including units that can accommodate the multiple generations that come together in large extended families, and for houses and house groups organized around shared courtyards and patios so as to better serve the child care and other common needs of unrelated households that, as Mike Davis notes in Magical Urbanism, sometimes move as entire “transnationalized communities.”

The insensitivity to culture evident in the more higher profile competing urbanisms is why I think Latino Urbanism—to the extent that it foregrounds issues of culture—should be closely watched as one Brand X alternative that’s capable of pointing the way to a more holistic, sustainable, and democratic approach to city-making. Leading advocates of Latino Urbanism like James Rojas, Michael Mendez, Teddy Cruz, and Katherine Perez think broadly and deeply about the kinds of design elements that best serve Latino cultural values and preferences. These include preferences for high density neighborhoods connected by public transport, for a variety of housing options including units that can accommodate the multiple generations that come together in large extended families, and for houses and house groups organized around shared courtyards and patios so as to better serve the child care and other common needs of unrelated households that, as Mike Davis notes in Magical Urbanism, sometimes move as entire “transnationalized communities.”

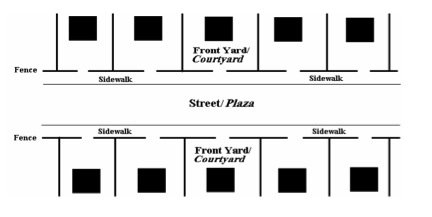

Schematic Comparison of House Form (from James Rojas, Latino Urbanism: A New Model for Sustainable Transportation)

In Latino Urbanism the boundaries between public and private space are also more fluid, with features like porches, verandas, and front yards serving as interaction-rich “transitional” or “intermediary” zones. Any formal bounding that occurs here is both social and practical. For example, fences are not of the stereotypical white picket variety often pictured in, or conjured up as a mental image of, the New Urbanism. Fences catalyze social interaction and serve not only to roughly demarcate private from public space but also to transform streets into plazas. They also routinely function to hang wet

laundry (thereby serving the cause of planetary sustainability) and goods for sale. Spaces often begrudgingly tolerated as necessary by-products of mixed use urbanism—e.g., surface parking lots (when they haven’t been replaced by parking garages)—allow other important contributions to an “informal economy” materialized as the stalls, pushcarts, and vans of street vendors. Parks and green spaces also function as surrogates for hard plazas and thus must be designed and equipped for intensive large group use including soccer games, family reunions, neighborhood parties, and community festivals.

Of course, such values and preferences are not exclusively Latino, and we’re guilty of stereotyping by other means if we imply that they are. Same goes for the values, preferences, and design features associated with the concept of Black Urbanism. That’s why we’re keen in this blog to highlight both difference and similarity in the ways that people from various cultural traditions construct and use the urban built environment. Intercultural Urbanism is interested not only in humankind’s shared predispositions for certain kinds of landscapes and built forms but also the novel and hybrid forms (nicely described by James Rojas as a syncretic vernacular) that spring from historically-contingent cultural interactions and encounters. Latino Urbanists are doing great work to prompt and promote better thinking about urban place-making within a broadly similar agenda. Such an agenda is becoming increasingly important as our cities diversify via immigration and, as reported just yesterday in The Denver Post, rural flight.

One Comment

Leave a Reply