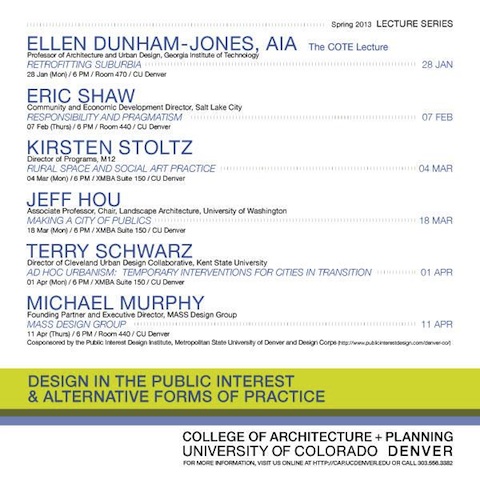

Retrofitting Dead and Dying Suburban Places

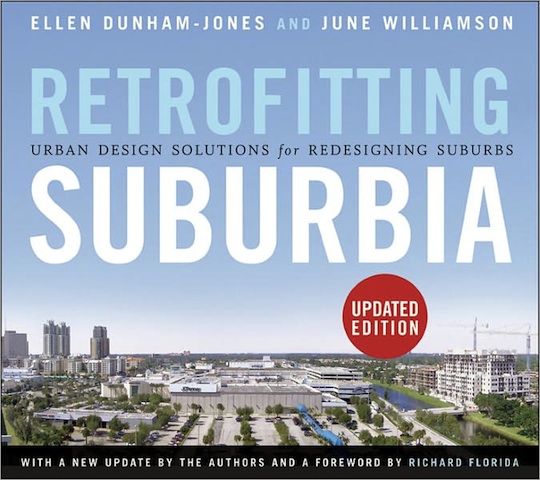

The College of Architecture and Planning at the University of Colorado at Denver is hosting a spring lecture series on “Design in the Public Interest & Alternative Forms of Practice.” Last week Ellen Dunham-Jones kicked things off with a lecture on “Retrofitting Suburbia.“ She essentially reprised and updated the arguments presented in her book with June Williamson that’s now in a revised edition. This included a comprehensive smart growth rationale for retrofitting suburban spaces and numerous examples illustrating three distinctive retrofitting strategies that Dunham-Jones referred to as re-inhabitation, re-development, and re-greening.

Dunham-Jones’s rationale for smart growth retrofitting of suburbia is commonsensical and compelling. Suburbia contains lots of vacant and underperforming spaces—to the tune of over 1 billion square feet. Climate change requires that we decrease the carbon footprint of these areas by investing in walkability. Incentivizing walkability will also help address America’s serious health problems around obesity. The 40% greater cost of municipal services in sprawling suburbs compared to urban cores, combined with economic recession and growing suburban poverty, recommends retrofitting for greater density and mixed use. There’s also an emerging cultural shift that’s best met by retrofitting for density and walkability: 77% of Millennials and 75% of Aging Baby Boomers want a more “urban core” lifestyle that has desired amenities within walking distance. All of this (among other things) makes traditional first ring suburbs, given that they are now more central than ever before, especially prime spots for smart growth and transit-oriented retrofitting.

Examples of promising suburban retrofits now number in the six hundreds, up from the 80 or so examples that Dunham-Jones and Williamson drew from in the first edition of their book. Re-inhabitation is exemplified by the widely-heralded conversion of an abandoned Walmart store into a public library in McAllen, Texas. Re-development of a “zombie subdivision” into a residential project including Habitat for Humanity townhomes serving low income people distinguishes Walkers Bend in Covington, Georgia. Re-greening takes a nice turn at Columbus (Ohio) City Center Park. Dunham-Jones also reaffirmed her favorable opinion of Belmar, a Denver area mall retrofit that serves as an extended case study in her book and that we previously discussed here. For Dunham-Jones Belmar has good construction, great connectivity, and sufficient variation in building styles to create a successful “sense of place.” In fact, Dunham-Jones applauded Denver for being a leader in regional mall retrofitting—we’ve “figured it out”—given that 8 of 13 regional malls have already been retrofitted and more are being retrofitted as we speak.

Denver’s several examples of suburban mall retrofitting offer an opportunity for evaluating how these places resonate with Millennial generation tastes. I asked students in my Fall 2012 Culture and The City course to evaluate three Denver suburban retrofits–Belmar, CityCenter Englewood, and the Streets at SouthGlenn–and pick the one they would live in if given choice. Only 20% chose Belmar, suggesting that they don’t share Dunham-Jones’s enthusiasm for this particular retrofit. Twenty percent chose the Streets at Southglenn. Interestingly, 60% went for CityCenter Englewood. Among the reasons: the development’s investment in outdoor sculpture, public library and art museum, and greater residential affordability. Students also appreciated CityCenter Englewood’s Light Rail transit connectivity (Belmar’s eight connecting bus lines did very little for them). In this respect my students disagreed with Alan Ehrenhalt’s assessment in his book The Great Inversion (the “Urbanizing the Suburbs” chapter, page 215), that CityCenter Englewood “turns its back on the light rail station and on transit oriented development in general.” Students appreciated the greater opportunity for encountering ethnic diversity at CityCenter Englewood, which some students explicitly linked to the nearby presence of value shopping retail outlets like Walmart. Walmart is apparently not an issue for these students as it is for citizens of their parent’s age living elsewhere in the city. In short, CityCenter Englewood struck my students as a more “authentic” urban place than the relatively more artificial developments of Belmar and Streets at SouthGlenn. Their experience in, and evaluation of these places was very different from that of the professional opinion-shapers.

Dunham-Jones ended her talk by noting several challenges facing the contemporary city. Cities must dis-incentivize sprawl. They have to do “instant urbanism” much better as concerns the visual interest and quality of design. Perhaps the biggest thing to “figure out” is how to make retrofits affordable and thereby prevent the displacement of poorer populations. Several of the cases Dunham-Jones presented looked very good in theory but in practice they only produced more gentrification. I would add that it might also be wise for suburban and urban retrofitters to do better testing of design concepts with the target populations that they intend to serve.

Leave a Reply