Are Garden Cities Sustainable?

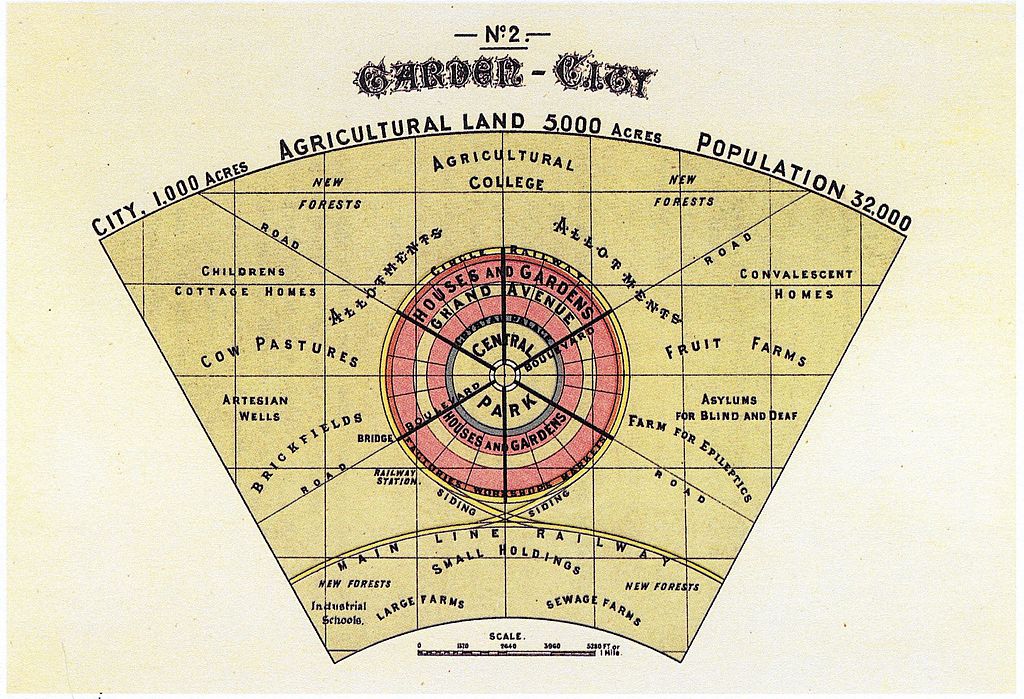

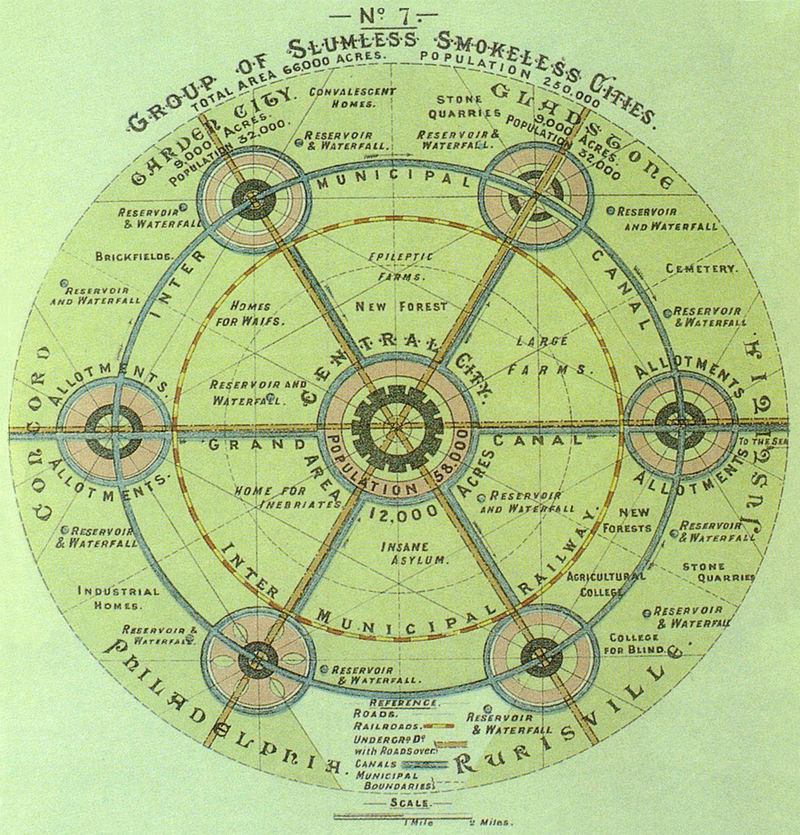

The answer to my title’s question depends, of course, on where they’re located, how they develop, and what we mean by “sustainable.” Certainly, Ebenezer Howard’s concept of the Garden City is one of the most influential planning models produced by 20th century urbanists. It remains so today, invigorated by Peter Hall’s updating of the concept in his 1998 book Sociable Cities: The 21st Century Reinvention of the Garden City (re-released in 2014 with co-author Colin Ward).

A recent special issue of the Journal of Urban Regeneration and Renewal (JURR) evaluates the concept of the Garden City for a rapidly urbanizing 21st century world. My colleagues Kyle Cascioli and Ron Throupe (both of the Burns School of Real Estate and Construction Management at the University of Denver) and I have a paper in the special JURR collection about how the Garden City concept is informing—consciously or unconsciously—new proposals for environmentally sensitive development here in the American West. This post abstracts our argument for a wider readership. It highlights some of the social and environmental sustainability issues associated with Garden City development, especially where they concern cultural diversity and inclusivity.

Sterling Ranch as Garden City

Sterling Ranch is a planned, mixed-use, “live-work-play” development located about 30 miles southwest of downtown Denver, Colorado. Sterling Ranch is not explicitly based on a Garden City model. However, it certainly conforms to the model. Although planned for just over half the acreage of Howard’s Garden City (3400 acres compared to 6000 acres), Sterling Ranch is nearly identical to the Garden City in terms of the resident population it is intended to serve: 31,000 people. A dense, amenity-rich town center and civic gathering place will transect outward—in concentric patterns as per Howard’s model—into clustered, tightly knit villages ending in rural, hillside ranchettes. Sterling Ranch will offer 30 miles of hiking, biking, and horseback riding trails, community sports facilities, small ‘pocket parks’ in residential areas, and access three regional parks and two state parks. These amenities will offer the “Areas of Tranquility” that Peter Hall counts as one of twelve key strategic policy elements for building his model of the Sociable City.

The developer of Sterling Ranch has negotiated with several builders who will produce, using distinctive and “authentic” styles, a range of different housing types including single-family homes, townhouses, and loft apartments. Channeling Howard’s belief that ordinary working people deserve affordable housing, a range of housing prices will also be available. Current marketing materials indicate that 35 percent of the house product will be priced below $200,000. Whether this counts as “affordable” is open to debate. Whether this bar will be maintained as build-out proceeds, given a historically-volatile economy, is uncertain.

Environmental sustainability is an explicit planning and design principle at Sterling Ranch. Howard’s contribution to sustainable planning is found in the Garden City’s eminent walkability. Walkability will certainly characterize Sterling Ranch’s clustered, mixed use residential villages. It will also govern wider transportation planning. Eighty percent of the planned 12,000 housing units in Sterling Ranch will have bus stops within easy walking distance. Shuttles will move commuters to Regional Transportation District (RTD) Light Rail stations, cutting down—at least in theory—the use of personal automobiles for travel to work. Telecommuting will be supported by the provision of auxiliary workspace units above garages and a state-of-the-art fiber optic network connecting the entire community. Bus lines, light rail, and high speed internet thus combine to serve as the “Inter-Municipal Railway” that linked Howard’s Garden Cities to each other. They also exemplify the “Top-Quality Linkages” that Peter Hall counts as another key strategic policy element for building the Sociable City.

The signature sustainability feature at Sterling Ranch will be its water conservation measures, some of which are pioneering. These include water efficient toilets, faucets, showers, and washers and dryers; a dual inside and outside water metering system with tiered pricing; artificial turf on sports fields; underground water storage beneath the sports facilities; water-saving native plants in landscaped areas; and, most significantly, technologies for harvesting and recycling rainwater. Almost 97 percent of the annual rainwater in the local jurisdiction of Douglas County never reaches a stream and is either absorbed by vegetation or evaporates. Sterling Ranch has received approval to harvest this rainwater for irrigation purposes. It is the first master planned community in Colorado to receive such permission. With these measures in place the water use per household at Sterling Ranch is estimated to be less than one third of that traditionally required by Douglas County. Sterling Ranch will reinforce its strong conservation ethos by dedicating a water conservation staff to develop water use guidelines and sponsoring programs to educate school children and community residents about the importance of conserving water.

While Sterling Ranch will not have the formal agricultural greenbelt proposed by Howard in his classic conception of the Garden City, its developer is partnering with Denver Botanic Gardens in a “Community Supporting Agriculture” project. This project will determine whether the development’s fresh produce needs can be met by community gardens instead of trucking in fruits and vegetables from afar. Sterling Ranch residents will be able to choose how they want to spend their allocated water budgets, selecting from various water-wise plantings or an edible garden.

Analysis

Sterling Ranch represents a unique vision rooted in a noble conservationist ethic. It’s an experiment in exurban development worth monitoring. However, even if it is successful the question will arise of how many Sterling Ranch-style Garden Cities can Western metropolitan areas accommodate? And, will this land use pattern promise any greater long-term environmental sustainability than high-rise densification projects in the urban core? At the moment it is not clear that clustered Garden Cities would offer, over the long term, any significant water savings compared to a single dense, vertical urban center.

Exurban development is also complicated by the fact that distance (as it affects urban core connectivity) and water are not the only relevant constraining variables. There’s also the matter of changing demographics. Online promotional materials for Sterling Ranch clearly target a demographic that is largely white, middle-class, and nuclear family-based. The greater United States, however, is approaching a tipping point as concerns the ethnic composition of its population. According to the United States Census Bureau, the country will become a “majority minority” nation by 2050. Like the rest of the United States Colorado is becoming increasingly diverse in terms of ethnic makeup. Over the last decade Colorado’s Hispanic population, the state’s largest minority, increased by 41 percent. The Asian population grew by 45 percent. The African-American population grew by 19 percent. By contrast, the white non-Hispanic population in Colorado increased by less than 10 percent. These minority population increases occurred throughout the state and not just in metropolitan areas.

This raises the question: Will domestic minorities be drawn to communities like Sterling Ranch, or any other Garden City-style exurban development, if cultural diversity is not a central planning and design concern? Sterling Ranch promises residential and public architecture that is “remarkable” and “authentic.” However, it’s a well-established fact that cultures vary in their design preferences for both residential and public space. The built form and aesthetics of civic and residential architecture carry particular cultural connotations and meanings and thus have differential appeal across ethnic groups. Other blog posts (e.g., here and here) consider these differences.

Ethnic groups also differentially value and assign meaning to water. Water, in many cultures, is a spiritual as well as an economic good. Case studies of water use from around the world have documented clear differences between Western, Eastern, Middle Eastern, and Indigenous cultures that are related to specific ritual practices. Thus, water management is not simply a technical matter. The different cultural uses and meanings of water need to be recognized by urban planners and basic service providers. Non-Western concepts of water as sacred can easily dovetail with a Western ethos of environmental sustainability. However, water regulating strategies like metering, recycling, and budgeting can conflict with particular cultural values identifying water as sacred and even as a basic human right. Certainly, management strategies like differential pricing of water based on intensity of use can easily discriminate against some cultural groups and contradict broader Garden City commitments to life quality and social equity.

The phased build-out of Sterling Ranch over a 20-year period certainly will allow for adjustments in planning, design, and marketing of the community as urban demographics and cultural preferences change. At the moment, however, how ethnic diversity affects urbanism and vice versa (i.e., how urban life is experienced by people of diverse cultural backgrounds) is an afterthought even in more progressive, sustainability-conscious urban planning circles.

The same can be said for how culturally diverse groups relate to the natural environment. There’s a significant literature suggesting that members of minority groups experience parks and other open spaces in different ways as a function of different cultural values and needs (see also here). This work identifies varying preferences among ethnic groups with respect to park attributes (e.g., water, trees, scenic vistas), the ratio of developed to undeveloped (“wild”) space, and patterns of use (e.g., as individuals vs. in larger groups, for recreation vs. relaxation, with vs. without food, etc.). Thus, even abundant green space that we assume is universally valued can still be unwelcoming to minority groups depending on how it is specifically designed.

This point is especially germane where planning for community gardens is concerned. These features may require an especially strong dose of intercultural literacy and sensitivity. Proponents of Garden City-style development are keen to address the challenge of urban sustainability by incorporating various forms of food production into their master plans. Andrés Duany, one of the founders of American New Urbanism, has proposed a variant of “Agrarian Urbanism” that is clearly predicated on Garden City ideals and finds concrete expression in the plan that’s being implemented at Sterling Ranch. Duany’s model development incorporates community gardens as a substitute for front yards and medium-sized farms as a substitute for traditional suburban amenities like golf courses. Duany is explicit in distinguishing Agrarian Urbanism by highlighting its emphasis on food production as a societal commitment.

Critiques of Agrarian Urbanism offer a cautionary tale for Garden City planning, including Sterling Ranch. They start with the observation that society is not equivalent to culture. Like water, decisions about food—what is grown, how it is harvested and prepared, how and where it is consumed, its symbolic meaning, and so on—are central to how a culture defines itself. For Jason King, cultural diversity in current formulations of Agrarian Urbanism appears only in the form of Hispanic laborers who will continue to be called upon to do the “dirty work” associated with the more labor-intensive forms of urban farming (albeit in the context of “a closer relationship with their employers”). Mike Soron has noted that Agrarian Urbanism risks “repurposing an economic underclass from ornamental landscaping and golf course maintenance to productive cultivation.” Finally, Greg Lindsay suggests that, if Agrarian Urbanism sticks with New Urbanism’s “traditional” town planning and architectural principles, this repurposing is likely to take place in a built setting strongly redolent of pre-1850s small-town, white America. In short, Agrarian Urbanism—and, by extension, Garden City-styled urbanism—risks producing a “New Feudalism” driven by a particularly narrow and potentially highly exclusive set of cultural expectations and prescriptions.

In short, if cultural inclusion, life quality, and social equity are important elements of what makes a city “sociable,” then designing built and open space for broad intercultural appeal should be a top priority going forward. Twenty-first century Garden City, Sociable City, and other urban models that seek to better integrate “town and country” could benefit from a greater understanding of how ethnic groups cognize their cultural and natural surroundings differently as a function of history and socialization.

Conclusion

Sterling Ranch has, in theory, considerable promise as a new form of Garden City for the 21st century American West. Its development model is underpinned, like Ebenezer Howard’s original Garden City model, by a strong vision. Its proposed suite of water conservation measures is a model for urban development in any part of the world where water is a key constraining variable. As noted, however, it would be wise to temper water planning with a clear understanding of how water is differentially valued and used by diverse ethnic groups. Sterling Ranch’s Community Supporting Agriculture project also provides a useful model of how developers can collaborate with the local scientific establishment to create community gardens that make both economic and ecological sense. Such collaboration was part of the central animating spirit of Howard’s original Garden City movement. But once again local cultural differences must be taken into account when deciding what kinds of fruits, vegetables, and other plantings these community gardens should contain. Finally, Sterling Ranch’s planned integration of green space and provision of multi-modal transportation options for residents are clearly features to be emulated elsewhere.

Whatever the admirable and exportable virtues of Sterling Ranch’s vision of Garden City-style development, the looming convergence here in the American West of Peak Oil, Peak Water, and “Peak Population”—in the sense of a rough compositional equivalence between white and non-white populations—could also recommend a future for western cities that is compact, dense, and vertical. In either case, greater awareness of cultural variation in ways of dwelling, using water, producing food, designing public space, and interacting with the natural environment will be important as cities in the American West are planned and developed. If “Peak Planet” is upon us, then the margin for error going forward is likely to be very small. The Garden City concept has a compelling intuitive appeal. Here’s hoping that planners and architects are up to the task of making a traditional and still desirable form of settlement more environmentally and interculturally attractive and sustainable.

Postscript: Another version of this essay is posted to Planetizen. The full text of the JURR paper mentioned above is available on the “Papers” page of this blog.

Leave a Reply