Cultural Inclusion as an Element of Neighborhood Planning

In a post at Better! Cities&Towns and also PlaceShakers and NewsMakers Howard Blackson succinctly summarizes what he considers the 5 basic elements of neighborhood planning, pitched as the “5 Cs”:

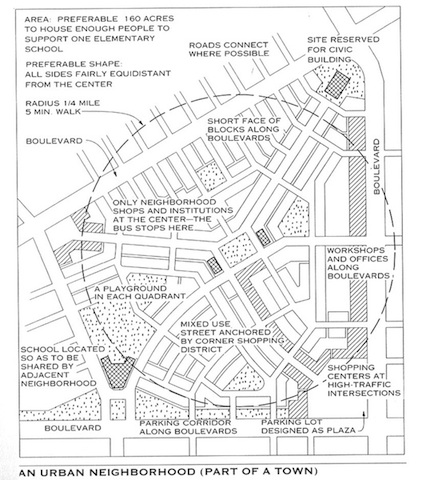

1. Complete: a mix of uses (allowing living, working, playing, lounging, eating, shopping, worshiping), bounded by a distinct edge.

2. Compact: a maximum 5 minute walk from the center of the neighborhood to its edge.

3. Connected: multiple modes of transportation (walk, drive, bike).

4. Complex: a variety of civic spaces (plazas, greens, recreational parks, natural parks), civic buildings (libraries, churches, community centers, assembly halls), private buildings (residences, offices, shops), and thoroughfare types (boulevards, avenues, streets, alleys, bike lanes, paths).

5. Convivial: supportive of human connections or relationships that are “friendly, lively, and enjoyable.”

I think that element #5 is a bit of an apple among the oranges. Physical properties of neighborhoods are one thing; human relationships can be quite another. Blackson clearly recognizes that there’s a relationship between built form and social interaction, that neighborhoods consist of many and varied communities, and that the human ability connect physically across these communities has something to do with our ability to, in his words, “thrive culturally.” But I’m not sure that conviviality is a neighborhood feature that’s as easily generated as the others. For example, the physical form of Denver’s widely celebrated New Urbanist neighborhoods too often signal, to non-Americans and ethnic “Others,” homogeneity and exclusivity. They are too often highly-ordered, all-too-predictable settings devoid of street life. Where such conditions exist a particular epistemology and theory of urbanism (and culture) is at work.

Alternatively, there’s something to be said for the messiness of city-life including, perhaps, the conflicts (or tensions) that can emerge when cultural differences are brought together. Such conflicts don’t have to end badly; they can be productively channeled. Efforts to resolve conflicts over the form and use of urban space can produce creative interventions in the urban fabric and new, collective forms of social and spatial belonging. Thus, I’d propose that Culturally-Inclusive replace Convivial as the 5th “C” on Blackson’s list. We’ve made a point on this blog of highlighting work (e.g., here) that explores the specifics of culturally-inclusive design from the standpoint of both process and product. Other blogs do likewise, such as Julian Agyeman’s Just Sustainabilities and Phil Wood’s Subversive Urbanism. Attention to this work might help New Urbanists, and others, better calibrate for culture. The task is to design not for conviviality, but rather for cultural-inclusion. We need settings that allow conviviality, cacophony, creativity, community, and even periodic chaos to flourish.

Leave a Reply