The Greatest Grid

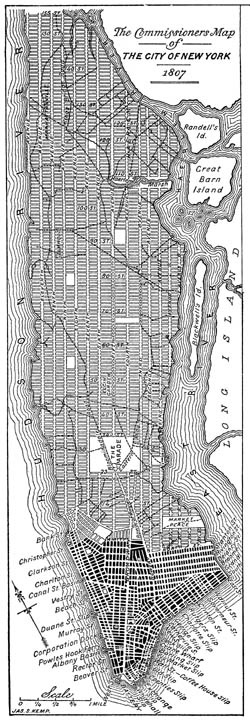

At least that’s what the Museum of the City of New York proclaims in the title of a new exhibition about the 1811 Manhattan street plan that’s currently celebrating its 200th birthday. It’s a bold claim, given the grid’s great antiquity as an element of urban planning. But then again, it’s New York.

Michael Kimmelman offered his analysis of the grid’s pros and cons in last week’s New York Times. Its imposed order is “heartless” to the extent that it eschews a single center and allows for very few grand public spaces. The grid is uniquely disposed to land speculation and, consequently, human displacement. I’d add that pedestrianizing any one cardinal boulevard or avenue risks marginalizing and deadening adjacent streets, as has happened (arguably) here in Denver with the 16th Street Mall. Other scholars (e.g., here)have argued that the grid–when considered in historical perspective–is most commonly associated with politically centralized, autocratic societies.

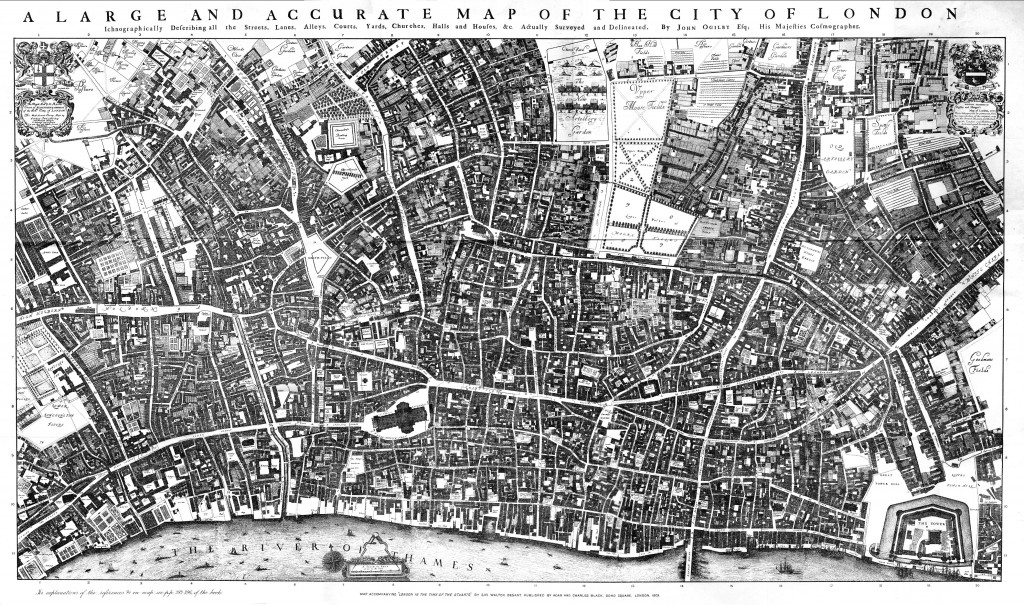

On the plus side, the grid is eminently flexible and adaptable. Mr. Kimmelman notes that Manhattan’s grid accommodated Central Park, the internal irregularity of which provides a nice contrast to an otherwise monotonous orthogonal order. The grid is nothing if not “legible”, allowing visitors to easily grasp a city’s layout. In so doing it makes a city instantly navigable. Indeed, Mr. Kimmelman argues that Manhattan’s grid invites long walks by residents and tourists alike, thereby contributing to urban environmental sustainability. In this respect New York contrasts with Berlin and London, whose historic agglomeration of villages “discourage easy comprehension and walking.”

For Mr. Kimmelman the New York grid—even without elegant squares, axial boulevards, and other elements that break up the monotony—can circumscribe neighborhoods and promote sociability in the Jacobsian sense. He asserts that the grid can still support the kind of block-to-block architectural and social variety that fosters “urban theatre” of the grandest sort. Moreover—and most extravagantly—he asserts that the grid is neatly predisposed to facilitating what I would call “intercultural integration.” Because of the grid’s legibility anyone—resident, tourist, and transient alike—can use it to take possession of the city, to make it their own. In Mr. Kimmelman’s words “anybody can become a New Yorker” and thus partake of that shared identity. New York’s grid gives physical form to the democratic idea of the urban “melting pot”—much more so than places like Rome, Hamburg, Copenhagen, or Tokyo.

I like Mr. Kimmelman’s article because it serves his admirable mission to put built form in a social context; to explore the relationship between what we build and how we live. In celebrating the grid Mr. Kimmelman in many ways channels Spiro Kostof, who in The City Shaped notes that there’s nothing inherently authoritarian or exploitative in a gridded plan. It can support and sustain “little villages” of the Jacobsian sort, and also be placed in the service of popular protest and dissent. For Kostof, how any urban plan functions socially depends on exactly how it is “fleshed out.”

Nonetheless, legibility and navigability is one thing; sociability and intercultural integration is quite another. Legibility and navigability certainly don’t guarantee the production of social interaction, shared experience, and mutual understanding. They are just as likely—if not more so—to produce greater atomization and fragmentation; to reinforce the status of urban space as—in the words of Richard Sennett—a “place of gaze” rather than a “scene of discourse.” Lower Manhattan’s Zuccotti Park has gained fame as a particularly lively discursive scene. But for all the physical virtues and social impact of what took place in Zuccotti Park, the eviction of Occupy protestors has sparked much discussion about the availability of genuine public space in New York. The future of civic discourse and dissent may require something more than the privately owned public spaces or POPS that emerged in New York purely as zoning anomalies.

So in contrast to Mr. Kimmelman I’d argue that the prospects for intercultural dialogue and integration are better in cities having plans that discourage legibility and easy comprehension. The prospects are better where people are challenged—as one online commentator on Mr. Kimmelman’s piece noted—to “use their brain” in civic navigation. London defies easy comprehension but there’s nothing like shared confusion about location and direction for stimulating conversation and a collective striving to meet the navigability challenge. Another virtue of London’s historic agglomeration is that memorials, monuments, and other physical vestiges of the city’s history are embedded in the urban fabric rather than exiled, as they have been in New York as a consequence of 1811 planning, to parks or–most famously in New York’s case–to an island in the middle of a harbor. It’s the potential to be ever-surprised by the discovery of these artifacts of cultural history that makes navigating the non-gridded city so joyful and satisfying. In my two brief stints living in London I came to feel more ownership of the city—and more kinship with Londoners—than I ever felt in all my years of growing up in New York.

This piece is also posted at the New York Urban website: http://newyorkurban.info/the-greatest-grid-intercultural-urbanism.

Leave a Reply