Monuments Matter: On the Destruction of Denver’s Public Statuary

A couple of the more controversial of these statues came down in the last few days, as part of the anti-racism and anti-monument fervor that’s now sweeping the country. I welcome such fervor and ferment. I’ve taught courses promoting anti-racism at my university for over 30 years. My research is focused on challenging racist urban policies that produce spatial and social inequality. I’m supportive of the protests sparked by the murder of George Floyd, and of movements for reforming the police and other civic institutions. I’m not necessarily against the destruction or removal of public monuments, especially those that cause emotional or psychological distress for fellow citizens. Politically motivated monument destruction is nothing new. Monuments have been targeted for destruction or removal throughout human history, going back to the Age of Pharaohs and beyond. However, it’s always appropriate to worry about indiscriminate vandalism given that material objects can play vital educational and consciousness-raising roles in efforts to challenge structures of oppression.

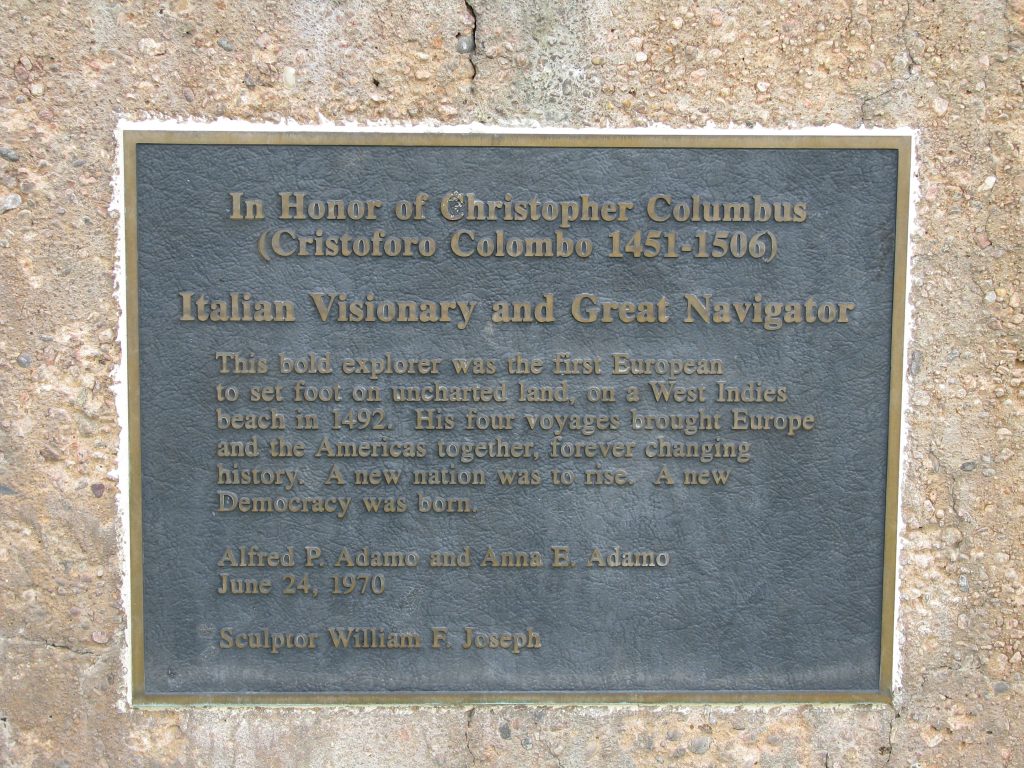

Denver’s monument to Christopher Columbus has been a lightning rod for criticism ever since it was installed in Civic Center Park in 1970:

The monument came down in the early morning hours of June 26. The Denver Post story (which contains some video of the toppling) reports that the American Indian Movement of Colorado—just one entity representing the community having the most to be aggrieved about—supports keeping the statue up but would like to change the name and the dedication. Certainly, democratic nation-building was the last thing on Columbus’s mind when he entered this hemisphere. Indeed, a better case can be made from ethnohistory and archaeology that democracy was a gift to us from Native Americans, not Europeans.

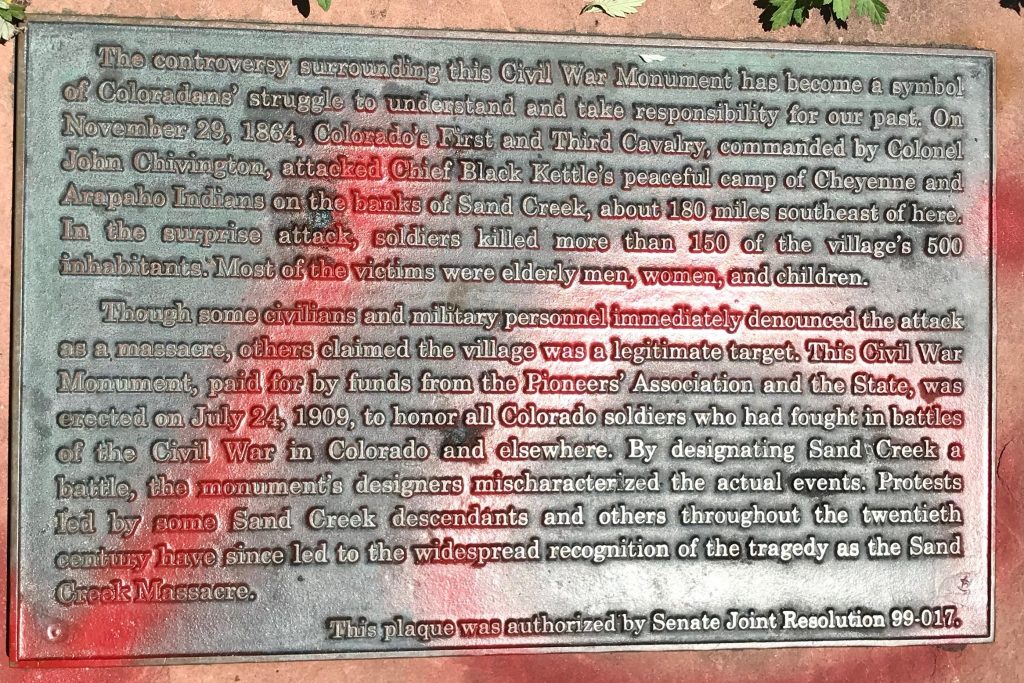

The day before, June 25, saw a more problematic toppling of the Civil War soldier’s monument in front of the state capitol. This monument lists the names of 279 Colorado soldiers who died in the conflict, along with 22 battles that include four fights with Native Americans. The most notorious of these episodes occurred at Sand Creek in November 1864.

A Denver Post story describes some of the graffiti that motivated the vandalism: “Defund Cops”, “Decolonize Denver”, and “Native America 1492.” One neighbor interviewed for the story sees the monument as a “symbol of white supremacy” that celebrates the genocide of indigenous people. There is truth to this, but the vandalism also produced collateral damage to a small plaque located at the statue’s base (visible in the pictures above) that correctly describes what happened at Sand Creek. Rather than a “battle”, Sand Creek was a massacre:

In 2013 I convened the University of Denver faculty committee that produced the report establishing Territorial Governor (and University of Denver founder) John Evans’s culpability for the massacre at Sand Creek. This report—a superior piece of critical and engaged scholarship by my DU colleagues Richard Clemmer Smith, Alan Gilbert, Billy Stratton, George Tinker, and Nancy Wadsworth, along with former Colorado State Historian David Halaas—was instrumental in prompting Governor John Hickenlooper to issue, in 2014, a formal apology for the Sand Creek atrocity that was endorsed by all other living ex-Governors. The damage to the plaque is disturbing because according to David Halaas it took a heroic effort back in 1999 just to have this small but extraordinarily important object installed by joint resolution of the Colorado Senate. More importantly, a descendant of Sand Creek, Even Laird Cometsevah, is quoted in the Post story as saying, way back in 1998, that white folks ought to be big enough to accept responsibility for this shameful past, and to use the monument as a teaching tool for improving who and what we are as a community. In so many words, Mr. Cometsevah recognized that the commemorative landscape is a vital “shadow curriculum” that can be used to instruct and inform.

In an earlier post on this blog I called attention to some alternative ways of dealing with controversial public statues, using the Confederate variety as a point of entry. This menu includes Retaining, Removing, Relocating, Re-interpreting, Replacing, and even intentionally Ruining the statues. Each strategy is best implemented via a process of community engagement so that all relevant parties and interests are part of the conversation. As I mentioned in the post,

The toppling of controversial monuments by a mob, or their removal under cover of darkness by public officials, is not an ideal way to proceed…Collaboration with others, and the thoughtful, self-conscious balancing of competing interests is key: balance between remembering and revering the past, between confronting the past and respecting the needs of the present, between commemorating particular histories and a common heritage, and between removing and preserving things.

Even in this emotionally super-charged moment I’m not sure that I’ve read anything in the justifications for, or press coverage of, monument destruction that causes me to change my mind. Cleansing a commemorative landscape to promote what’s perceived to be a more progressive view of history is no less problematic than blindly preserving an existing landscape in the name of an all-heritages-are-equal ideology. The built environment is too important as a shaper of human psychology and identity to be treated so simplistically. And, as our wise Native American interlocutors suggest, too important as an educational tool. Re-making the commemorative landscape in a way that’s cognizant of multiple criteria, interests, and objectives—without forgetting the contradictoriness of human beings and the horrors of which they are capable—is our responsibility as citizens of a diverse, multi-ethnic society.

This essay is dedicated to the memory of David Halaas (1941-2019).

Leave a Reply