Public Art and the Urban Experience: A Retrospective

The Biennial of the Americas just kicked off here in Denver. The Biennial was launched in 2010 by then Denver mayor (now Colorado governor) John Hickenlooper as a grand forum for talking about politics, education, business, the arts, and other subjects of interest to citizens.

This year’s Biennial theme is NOW!. It’s billed as an analysis of the present in light of the history that got us here and our plans for going forward. The three main organizing topics are Leadership, Business Trends, and Infrastructure. Several of these topics will be considered by a special panel of mayors (Denver’s Michael Hancock, Calgary’s Naheed Nenshi, and former Bogotá mayor Antanas Mockus) who will address “The Return of the City-State.” These civic leaders will discuss how cities are operating on the frontlines of many contemporary global challenges including growth, security, and trade.

As usual, many artists from throughout the Western Hemisphere will showcase their work at Biennial venues, challenging us to look at cities and the world differently. They will be hard pressed to match the 2013 Biennial‘s very intimate connection of public art to commentary about the urban condition. A retrospective of that still-timely exhibition is the subject of this post.

The 2013 Biennial, organized to the theme of Draft Urbanism, featured billboard pieces by more than 30 artists, poets, and philosophers, covering a 10-square-mile area of the city. Each billboard was annotated with a museum label. The outdoor exhibition, mounted under the auspices of Executive Curator Carson Chan, was intended to re-sensitize citizens to the metropolitan experience. It sought to turn the city into a “space of inquiry” in hopes of prompting the public to examine it with “fresh, discerning eyes.” It provided an opportunity “for a communal reckoning of our shared environment, and to ask everyone to be alive to their surroundings.” The word “Draft” in the exhibition title implicated the city as always in a state of becoming, and the power of citizens to shape it through human agency.

Denver’s billboard artists reflected on many dimensions of the contemporary urban condition that continue to be salient today. In his review of the billboard exhibition David Hill of the Architectural Record opined that the artwork felt “scattered, both geographically and thematically.” But this really depended on how you interacted with it. As an anthropologist I found some compelling themes to connect the various pieces. And, in my experience, these themes were often enriched by the remote location and immediate context of the particular piece. The distribution of the art invited citizens to physically visit parts of Denver where they might not ordinarily venture. Indeed, that was one of the most important accomplishments of the exhibition. Visiting the art in relatively unfamiliar parts of town got me off the beaten track and out of my usual routine and comfort zone.

My retrospective begins with this billboard from Douglas Coupland that was located on what the Architectural Record called “a lonely stretch of road in an industrial area north of downtown.” That road is Brighton Boulevard:

As described by the exhibition’s curators, Welcome to Detroit is a

“Reaction to Detroit’s long term deindustrialization and depopulation—as well as a chilling foreboding [of] new meanings for a city whose twentieth century raisons d’être have largely vanished. Coupland’s slogan functions as a welcome sign much like those one would find entering other cities of speculation like Las Vegas and Reno, as well as a welcome sign into a new and unmapped era in human history. He says “Think of Detroit as one million primates needing 2,500 calories a day sitting on a cold rock in the middle of the North American continent, with nothing to do all day. It is an unparalleled crisis of purpose, and Detroit just happened to get there first—but sooner or later we’ll all be there.”

The piece worked pretty well given the increasingly dark and threatening day that I visited, and especially when framed against the backdrop of Denver’s remaining industrial center. That center is now experiencing a feeding frenzy of commercial property sales as developers seek to turn industrial buildings into apartments, offices, restaurants, and breweries.

Playing on the theme of urban dystopia, Pia Camil’s Rise Into Ruin was located on an even more isolated stretch of north Broadway, adjacent to the gated and barbed-wired scrapyard of an electrical supply company:

According to the curators Pia Camil’s practice explores

“…the urban ruin—including photographs of halted projects along Mexico’s highways. The image shows the opposite side of the billboard; that is, the backstage, riddled with chaos, detritus, and deterioration. Camil’s work, however, is imbued with a sense of hope, something that is reinforced by the vibrant colors. The phrase “rise into ruin” suggests the cyclical nature of the world, the phoenix that rises from ash to become, inevitably, ash again.”

In a stretch of west Denver’s Federal Boulevard dominated by automobile repair garages and pawn shops, Brazilian artist Ricardo Domeneck offered Continental Scar Tissue, a poetic commentary about history that riffed on the American urban grid. The billboard’s message is reinforced by the name of the auto service shop that’s located right above it:

For the curators,

“Domeneck’s poem follows a precise measure like downtown Denver’s city grid. It traces both the geography and history of the Americas, mixing the current locale with his native Brazil, illustrating subtle tensions. In the first two stanzas Domeneck jumps from one location to the other, juxtaposing landscapes, histories, and cultures. With this hopping from one to the other, the trail of tears from the Araweté tribe can be located in São Paolo as well as in Colorado ski resorts, as if this violence can be seen and felt just about anywhere. Indeed, one of the poem’s strengths is its ability to entwine loss and celebration. By the time we reach “Centennials for the Americas” the poem slowly drifts out of a specific location to the idea of America, claiming that the transcendentalist thinkers Emerson and Thoreau are dead.”

Placed a couple of blocks east of this site, on Decatur Street in a food delivery company’s gated and barbed-wired parking lot, was a piece by Dmitri Obergfell called Free Money. The slogan “The Golden Age Was The Age When Gold Didn’t Reign” is taken from a radical 20th century movement called the Situationist International, and was originally written in graffiti throughout Paris 50 years ago. In this early 21st century iteration it appears in conjunction with a burning sports car:

For the exhibition’s curators Obergfell’s critique is clear:

“Cars are a symbol of status and freedom in America. Nevertheless, they are also a necessity—in Denver, as in other American cities like L.A., an automobile is a basic requirement to navigate the urban landscape. Obergfell, then, seems to be calling for a change in the system of values—perhaps proposing that our values are entangled in places where they should not be. But questions arise: does reproducing text originally hand-painted on walls validate its claims when it is printed as a billboard slogan? Does it subsume it into a culture of consumption and spectacle?”

The class divisions and racial segregations produced by consumer culture and speculative capitalism—inequalities that are very effectively reproduced by even the (theoretically) egalitarian urban street grid—is captured by Isabella Rozendaal in her New Orleans 2011, situated on Champa Street in central Denver:

For the curators, Rozendaal’s piece

“…takes the innocuous, a road sign at an intersection, and charges it with the political. Every city is replete with clues as to how it can be read, and Rozendaal’s photo—which has the name of the city where it was taken—exposes New Orleans as a city clearly divided by racial and religious lines…Rozendaal reveals the store of information that is hidden in plain sight but crystallized when reexamining everyday objects through art.”

This particular piece was enhanced by its location in a vacant lot at the precise juncture of three electoral precincts within Five Points, a historically black neighborhood. It drew additional strength from the opposition of a rehabbed apartment building to the right of the billboard and the dilapidated houses directly across the street on the left. Rozendaal’s subject obviously remains relevant given the recent troubles in Ferguson, Baltimore, and Charleston.

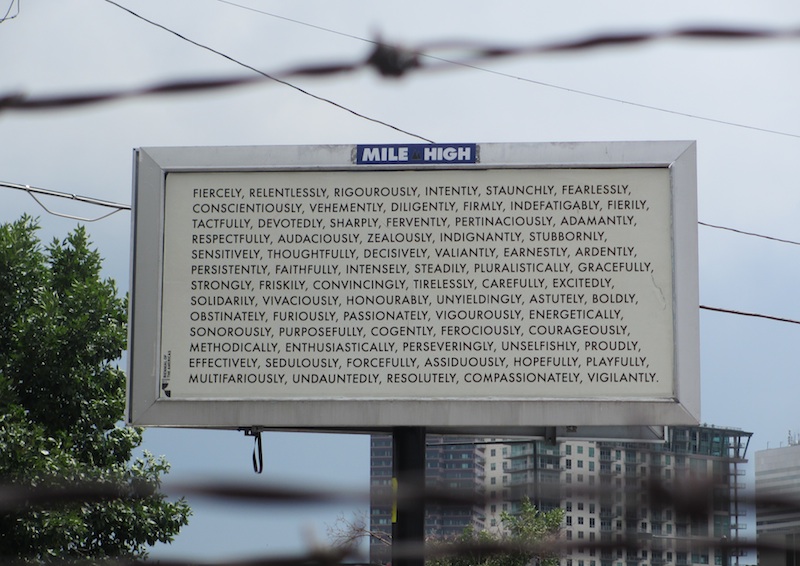

Also in central Denver, the Canadian artist (of Turkish descent) Erdem Taşdelen‘s Postures in Process reflected on another aspect of today’s urban condition, the popular uprisings that have been breaking out worldwide in response to government efforts to privatize public space as well as the global deepening of social inequality. The piece was inspired by the insurgency in Istanbul’s Taksim Square. Looming (appropriately) above a gated and barbed-wired Enterprise Car Rental lot on (appropriately) Broadway, Taşdelen’s work presented a string of adverbs that describe the strength and fortitude of those who were protesting the privatization of public space in Turkey and who continue to do so around the world:

Finally—and staying with the theme of popular insurgency—there was this remembrance, from Steve Rowell, of the early 20th century working class struggle at Ludlow, Colorado. I’ve written about the Ludlow Tent Colony—now a National Historical Landmark marking the 1914 killing of striking immigrant coal miners by the Colorado state militia—because of what I take to be its relevance for theorizing, and tactically implementing, intercultural and cosmopolitan city ideals.

For the curators,

“Ludlow is now a ghost town and a sense of conflict and desolation is apparent in the photograph of a man [actually, a Colorado militiaman] inside an odd-shaped grave [actually, the tent cellar where the bodies of 13 suffocated women and children were found after the colony was burned in a militia effort to break the strike], with one hand jutting out…Nearly a hundred years later, Rowell reminds us that this struggle is still present. Rowell…aims here to convey a site of memorial through an economy of means.”

Ludlow is located on Brighton Boulevard just a few blocks south of Welcome to Detroit. Thus, the piece brings us back to the historically (and now rapidly regenerating) industrial heart of north Denver, and the related themes of urban struggle, ruin, and renewal. Like the other pieces, Ludlow drew power from its evocative context and associations. In this case, the piece was squeezed into a small, dark, cellar-like space between a Latino grocery store (there was a significant Latino presence in the southern Colorado coalfields both during and after the troubles of 1913-1914) and the fenced-in house next door.

For a social scientist like myself there was a lot to like in Draft Urbanism‘s outdoor exhibition of artwork. The individual contributions were rich with meaning that one could construct for oneself. This made the search for the art particularly rewarding. The main point of this retrospective is to suggest that there’s an excellent model of public engagement here that other cities and urban artists might want to emulate if they’re interested in promoting critical thought about the urban condition. Whether there’s anything in these sorts of artistic interventions that can be internalized and applied by urban planners and civic leaders is a provocative and potentially useful question. Certainly, the 2013 Biennial’s public art exhibition suggested that the problems of the contemporary city are going to be a lot harder to solve than many politicians, pundits, and prognosticators think. And that makes it a tough act for the 2015 Biennial to follow.

Leave a Reply