Trayvon Martin and the Psychosocial Impact of Gated Communities

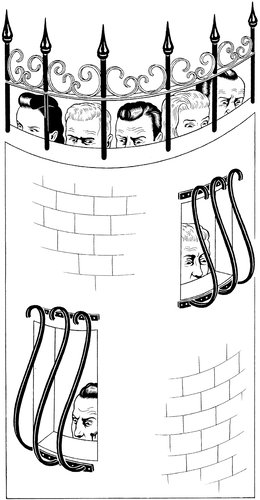

In March 2012 Better Cities and Towns posted an article by Robert Steuteville suggesting that a “poorly planned, exclusionary built environment” was a factor in Trayvon Martin’s death at the hands of George Zimmerman. Steuteville posited that gated communities create fortress mentalities characterized by paranoia and suspicion of anyone who looks out of place within the walls. Steuteville implied that if the site of the Martin shooting—The Retreat at Twin Lakes—had been more walkable then the Trayvon Martin tragedy might have been averted. In a post on this blog I noted, using data from a couple of Denver neighborhoods, that even highly walkable communities have their issues with crime and personal assaults.

Yesterday, in recognition of the Zimmerman trial verdict, Atlantic Cities re-posted an essay by Sarah Goodyear from April 2012 that was originally prompted by the Steuteville piece. Goodyear reported that available research is inconclusive about whether paranoia and suspicion are promoted by life behind the gates. There’s better evidence that gates do not deter the kinds of crimes that are experienced in other kinds of communities. However, Goodyear quotes a bit of a UN Habitat Report suggesting that gating does have broader social impacts. According to the report,

[The] significant impacts of gating are seen in the real and potential spatial and social fragmentation of cities, leading to the diminished use and availability of public space and increased socioeconomic polarization. In this context, gating has been characterized as having counterintuitive impacts, even increasing crime and the fear of crime as the middle classes abandon public streets to the vulnerable poor, to street children and families, and to the offenders who prey on them. Such results also tend to broaden gaps between classes insomuch as wealthier citizens living in relatively homogeneous urban enclaves protected by private security forces have less need or opportunity to interact with poorer counterparts.

Reader comments on the re-posted Goodyear piece include a few different takes on the issue. Here in Denver, “chris1059” acknowledges that, while no community is perfect, there are certain virtues to gated living:

When I moved into my gated community a couple of years ago, my wise neighbors were quick to note that this community would not make me safer from crime. I knew that. However, an enormous benefit of the gated community is that is drastically reduces nuisance traffic in the neighborhood. Fewer ice cream trucks, door to door brush salesmen, etc. A Mormon missionary the other day was quick to point out to me after interrupting my dinner that the court has given him an exemption from the word “soliciting”, so the gates don’t keep the Mormons out. But a 90% reduction in other nuisance traffic is well worth the extra money I paid for my house.

Alternatively, “dfasfgl” in Los Angeles describes the downsides of gated living in a way that offers qualified support for Steuteville’s argument:

I live in a gated community. Unfortunately it is a decidedly working class gated condo complex in Culver City…The only people who aspire to live here are our neighbors in Inglewood. But the people who live here have a weird paranoia anyway. Mostly it is my elderly neighbors. Boredom slowly creeps into insanity while they sit on their couches growing more wrinkles. They have nothing better to do all day except spy on their neighbors and freak out and make some drama at the sight of a stranger. When that is over they yell at the children about making too much noise. Poor Trayvon would never have been shot if he climbed the fence to cut through my condo complex. But if he hung his laundry out to dry, they would make him wish he was dead.

Self-identified urbanist “k_bee” urges cautions against invoking this kind of “spatial determinism” and, alternatively, emphasizes the role of culture in conditioning how people think both within and beyond the gates:

Our built environments are shaped by our cultures, not the other way around… What we need to talk about are the mentalities and fears that suggest we are in danger, that inform our ideas of who may be dangerous to us, that tell us what steps seem necessary for personal protection, or that teach us we need to have the absolute right to self-defense without any duty to retreat. How do those mentalities produce certain modes of living? How do they affect the way we perceive and use public space, and how we choose to encounter our neighbors?

These are excellent questions. But we can allow the causality to go both ways without succumbing to a crude spatial determinism. In a response to “k_bee” commentator Josh Michtom suggests that

You’re surely right that the growth of living arrangements that put people at a remove from others is caused by culture, but it also reinforces attitudes across generations…As the years pass, the realities of [these] people become more abstract, and for children the abstraction is all the greater. The result is a whole class of people who see danger in the unknown in a way that is fairly disconnected from reality. It is a view of the world that sees more peril and more need for aggressive self-defense than I think is warranted, a view that makes stand-your-ground and concealed carry laws feel more necessary than they otherwise might, and a view that can lead an arguably well-intentioned neighborhood watch volunteer to shoot an unarmed teenager.

For her part, Sarah Goodyear concludes that we will likely never know if the built environment played a role in Trayvon Martin’s death. However, that particular jury is still out. Assuming a reciprocal relationship between built environment and culture–or between place and psychology–might usefully frame future inquiries into the issue.

Leave a Reply