How Many Rules Are There For “Smarter” Smart Growth?

Bill Adams identifies ten rules that incorporate some of the original Smart Growth Principles while punching up those that urge greater respect for the character, identity, and established planning processes of an existing community. He also adds a “Bonus” 11th rule which is to preserve and enhance the existing density and urban fabric.

Responding to Adams, Kaid Benfield says there are 15 rules. These include Adams’ 10 plus another 5 that are about greening urban buildings and infrastructure and designing for age and family friendliness. Like Adams, Benfield adds a Bonus 16th rule:

Pursue communities suitable for a diversity of incomes, housing types, ethnicities, and old/new residents. That’s the future of America; surely it should also be the future of smart growth.

Of the 20 commentators on Benfield’s piece David W. Goldberg hits the nail squarely on the head:

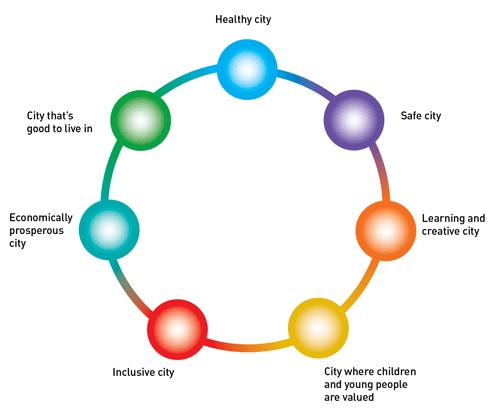

Kaid, thank you for adding 16, though I would like to see it as #1. Every day I am surprised by how long it takes my planner colleagues to get around to talking about people… When we planners are at our best, we’re placing people and place together. Smarter, Smart growth matters because OUR lives depend on it. A set of updated rules that did this might begin with “Communities where diverse households of all ages, types, culture and incomes call home, and have access to the resources they need to lead fulfilled lives, and share in the benefits of growth.”

Mr. Goldberg has it exactly right. Diversity must become more than a “bonus” bullet point, or an add-on, or an afterthought. It should be Priority #1. And maybe it’s the only “smarter smart growth” rule that matters because the others have become so well-rehearsed and even—no pun intended—pedestrian. They fail to directly address today’s and tomorrow’s most compelling demographic reality which is the growing ethnic diversity of urban populations.

To make headway in meeting this challenge we should problematize that which is held constant or taken-for-granted by both Adams and Benfield. Specifically, the concepts of “community” and “neighborhood identity.” These are more complicated entities than most planners—and even most “community” members—think. At least that’s my experience from watching the planner-developer-citizen dynamic at 9th and Colorado here in Denver. Previously on this blog I’ve channeled the geographer David Harvey’s classic statement about the rhetoric of community that’s used by some planners and developers to justify a particular kind of “urban village” development. The same can be said for those who frame smart growth in terms that emphasize a community’s “character and identity”:

Community has always meant different things to different people…the idea attracts, drawing support from marginalized ethnic groups, impoverished and embattled working-class populations…as well as from middle- and upper-class nostalgics who view it as a civilized form of real estate development encompassing sidewalk cafés, pedestrian precincts, and Laura Ashley shops. The darker side of this communitarianism remains unstated: from the very earliest phases of massive urbanization through industrialization, “the spirit of community” has been held as an antidote to any threat of social disorder, class war, and revolutionary violence. “Community” has ever been one of the key sites of social control and surveillance, bordering on overt social repression. Well-founded communities often exclude, define themselves against others, erect all sorts of keep-out signs (if not tangible walls)… “Racism, ethnic chauvinism, and class devaluation…grow partly from the desire for community” such that “the positive identification of some groups is often achieved by first defining other groups as the other, the devalued semi-human.” As a consequence, community has often been a barrier to rather than facilitator of progressive social change… All those things that make cities so exciting–the unexpected, the conflicts, the excitement of exploring the urban unknown–will be tightly controlled and screened out with big signs that say “no deviant behavior acceptable here.”

Planners, architects, neighborhood associations, city leaders and others must start attending to the underclasses who are left out of discussions of any kind of growth, smart or otherwise. These folks are silent and/or invisible because they usually don’t have the time or means to participate in the “community” conversation. Moreover, they are not ordinarily targeted by official outreach efforts. It’s almost certain, however, that the urban underclasses desire better jobs, quality affordable housing, amenities that include value shopping alternatives, a variety of transportation choices, and perhaps other things that so far are known only to them. It’s a good bet that our marginalized communities would also value a bit more variety in the design of private and public built spaces, as well as more flexibility to use these spaces in keeping with different cultural values and needs .

In short, if Smarter Smart Growth Rule #1 (after Goldberg) is Pursue communities where diverse households of all ages, types, culture and incomes call home, and have access to the resources they need to lead fulfilled lives, and share in the benefits of growth, then “Bonus” Smarter Smart Growth Rule #2 (after Saitta) is Pursue conversations about the private and public built environments of communities that are socially and culturally inclusive. Lessons on how to do this are available if the purview becomes much more global and intercultural.

Leave a Reply