Venice Seminar on Intercultural Place-Making: A Report and Some Reflections

It was an honor to participate in the recent Intercultural Place-Making Seminar sponsored by The Council of Europe’s Intercultural Cities Programme and held at the Palazzo Badoer, Università IUAV di Venezia. The seminar’s central organizing question was how urban planning and architecture should take account of ethnic and cultural diversity. How would planning and architectural design look different if informed by an intercultural approach predicated on cultural inclusion and interaction, as opposed to a multicultural approach predicated on cultural separation and coexistence? Seminar participants included academics and practitioners. A paper by Phil Wood circulated in advance of the seminar served as a conceptual touchstone for the discussions. My contribution was an academic perspective on intercultural place-making in the United States, and is posted to the presentations page of this website.

The small group of invitees (around 30 people) made for good interaction and discussion. My most important takeaways—which may not be shared by other participants—include the following:

1. Points of Consensus:

- Cultural diversity is a good thing that brings certain benefits to cities—among them greater social and economic vitality and creativity—if its power can be harnessed and “hybridity” encouraged. Diversity produces new ways of thinking, being, and doing that better equip human populations to deal with changing circumstances and conditions. However, harnessing diversity’s advantages requires improved intercultural literacy or competency; i.e., a more nuanced understanding of the nature, sources, and consequences of cultural difference. Participants were keen to frame the issue of diversity as an opportunity or challenge rather than as a threat, nuisance, or problem.

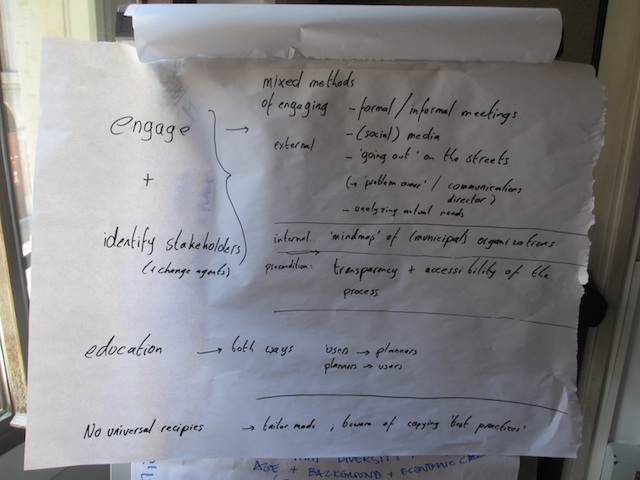

- The intercultural city is co-created or co-produced. There can be no substitute for working with local communities in generating “place.” Planners must discover what communities need rather than assert what they think they need. The intercultural city is fluid and “always on the move.” Thus, particular ideologies of planning and design can’t be imposed top-down. Planners must trade on their powers of empathetic understanding and be good listeners. Indeed, listening was widely embraced as the essential key to good place-making. To the extent that citizens don’t communicate in the language of professional planners we need creative ways to solicit the stories and memories that can inform good planning and design (e.g., asking adults and children to visually represent, in paintings, sketches, and models, their image of the “good city”). Good planners function as facilitators, mediators, and conflict resolvers.

2. Points of Contestation:

- To what extent should making “reasonable accommodation” (sensu Mohammed Qadeer, whose work is favorably cited here) for ethnic difference be an explicit part of urban planning? Is this a viable intercultural strategy? Or does reasonable accommodation simply reinforce the multiculturalism from which we’re looking to escape; i.e., ethnic segregation and the kind of identity politics that too often impede the cultivation of shared citizenship? It strikes me that we need a balance between making accommodations that signal to a city’s new arrivals the presence of a familiar support network and designing the fully democratic public spaces that allow everyone to feel at home.

- Are there elements of urban design—i.e., some cross-cultural common denominators of taste—that everyone will like? I sensed skepticism about this but I think it’s an interesting question that’s worth investigating. Doing so, however, will require broadening the scope of inquiry to include some disciplines that aren’t ordinarily consulted by planners, designers, and architects. At the seminar I was continually inspired to think about what the “deep time” perspectives of evolutionary psychology and archaeology can contribute to the intercultural place-making conversation. I’ll amplify this idea in a couple of future posts.

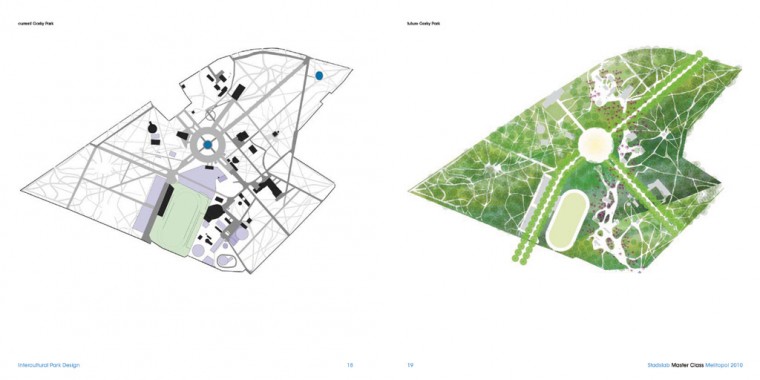

The seminar was highlighted by discussion of three specific projects explicitly informed by intercultural city principles. One is redesign of the main city park—Gorky Park—in Melitopol, Ukraine. Design team coordinator Marc Glaudemans of Stadslab European Urban Design Laboratory presented the plan. Melitopol is an Intercultural Cities Programme pilot city. It is home to over 100 nationalities. Significantly, the redesign of Gorky Park as an intercultural space was based only on the cultural values that its designers took to be commonly shared by all of the people who cohabit Melitopol. These shared values are found—to invoke a wonderful descriptive phrase from participating architect Beatriz Ramo found in the project’s final report—in the “magnificent rituals of the simple” (page 13). These rituals include celebration (apropos for Melitopol given the number and variety of feast days celebrated by the city’s residents), love (given that the city is known for the large number of wedding shops to be found on its streets), and sport (given that sport is one phenomenon that brings diversities together world-wide).

The park redesign consequently involves some distinctive physical features. A circular central area anchors the plan. This space can host dances, markets, concerts, festivals, and summer cinema. The central circle is surrounded by a blue bench that can be shared by up to 1000 people. There’s a “Wedding Lane” that extends from the park’s eastern edge to the center, with landscaping prominence given to white-colored flowering plants. “Sport Lane” starts at the western entrance and also extends to the center circle. It collects all of the existing sport installations of the park. The distinctiveness of the Melitopol locality is signaled in some other physical ways. Cherry trees and beehives are proposed to reflect the city’s civic identity as a famous producer of cherries, other fruits and vegetables, and honey. In Stadslab’s final report Marc Glaudemans nicely captures (page 4) the rationale at work:

We have no naïve belief in the power of architecture to fundamentally affect people’s values or behavior, but if the basic conditions are there, the architecture of the park can reinforce such behavior and provide an immensely richer environment for being and living together in the city.

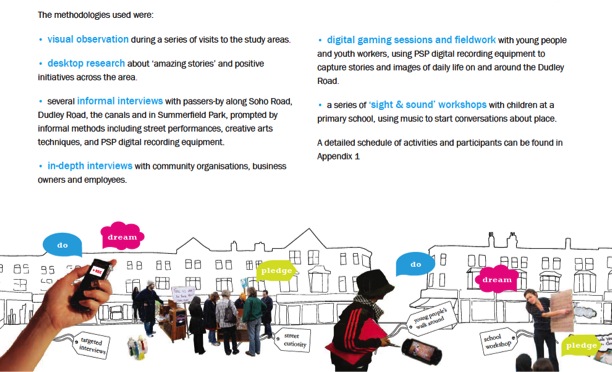

In discussing Urban Living’s Sense of Place Project in northwest Birmingham, England Noha Nasser of the University of Greenwich highlighted the outreach methods used to engage a diverse public in the process of neighborhood regeneration; i.e., in a process of co-creating the city. The population of the Soho-Dudley Road area is over 70% black and minority. The neighborhood is a reception area for immigrants, and transiency is high. The population suffers from unemployment, inter-ethnic tension, and the kinds of social conditions that produce segregation, despair, and gang culture. Multiple methods were employed during the mapping phase of the project to gain understanding of what the place means to this diverse population of residents and to collect their suggestions for improvement. These methods included visual observations, informal and in-depth interviews with passers-by and business owners, participatory arts workshops for kids that used images and music as prompts for starting conversations about place, and a variety of other social media and digital tools. A couple of “catalyst events” brought the community together to discuss findings and aspirations. A one day “Living Room” event transformed Soho Road into a public space that allowed goals-setting and networking discussions. The “Community Journalist Taster Workshop” recruited locals to disseminate community news and information in exchange for training in digital skills.

One particular finding indicated that the strongest affection shared among area residents was for the local park and library. This adds more evidence for Phil Wood’s claim in the circulated pre-conference paper (page 8) that, when people are asked to identify popular intercultural spaces:

…the places mentioned with most frequency [are] not the highly designed or engineered public and corporate spaces but rather the spaces of day-to-day exchange such as libraries, schools, colleges, youth centres, sports clubs, specific cinemas, the hair salon, the hospital, markets and community centres. These are the spaces of interdependence and habitual engagement where (what Ash Amin calls) “micro publics” come together and where (according to Leonie Sandercock) “dialogue and prosaic negotiations are compulsory.” In these places, “people from different backgrounds are thrown together in new settings which disrupt familiar patterns and create the possibility of initiating new attachments.”

The project’s signature result, however, is the “Do Dream Pledge” co-production technique. This technique is emboldening residents to take ownership of their community; to share experiences, communicate their hopes for the future, and seek new ways to work with others. It may also encourage them to begin to identify as citizens who have a shared stake in the collective good of the neighborhood rather than as members of a distinctive ethnic group. The Sense of Place Project final report persuades that the process employed in this case was not simply “consultation” but rather “a real engagement in citizen-driven master planning.”

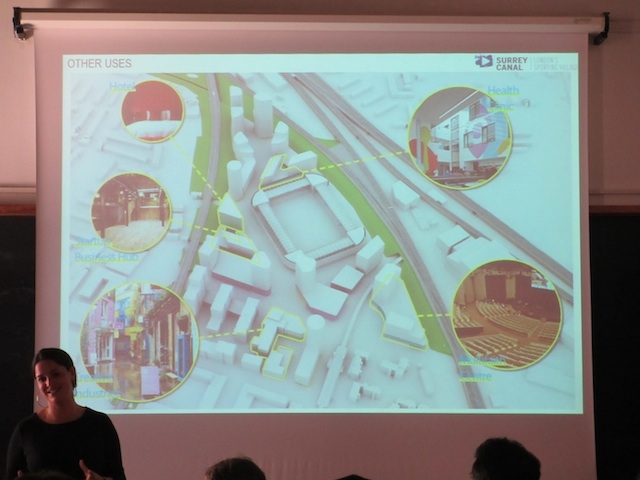

Finally, Surrey Canal in southeast London is a mixed use infill site that takes its lead from the area’s “sporting heritage”, especially the presence of Millwall Football Club. Jordana Malik of the Renewal Group development company discussed the plans. They include an improved setting for Millwall F.C.’s stadium and a leisure district with shops, cafes, and restaurants to serve not only football fans but also other residents of southeast London. There’s provision for a new community park and affordable housing. Significantly, however, Phase 1 of the project will focus on construction of a Faith & Community Center. The Center will house a number of faith organizations and affiliated community facilities including a rentable meeting hall with capacity for 1000 people, a new home for the South London Multi-faith and Multicultural Resources Centre, classrooms, offices, café, and exhibition spaces. The Faith and Community Center brings both reward and risk as articulated by Renewal’s partner in the enterprise, the University of Manchester’s Multi-Faith Spaces [MFS], Symptoms and Agents of Religious and Social Change research project:

Within these spaces divergent worldviews might be brought together, with potential reconciliation between belief systems occurring. Some even view MFS as places where new religious practices might thrive. Additionally, MFS have received overt political endorsement, with the Department for Communities and Local Government (DCLG) noting the importance of ‘shared spaces for interaction’. Here MFS are viewed as tangible manifestations of tolerance and pluralism, within a socio-religious landscape characterised by a certain degree of fragmentation. Yet issues arise as to whether these spaces are being constructed to promote narrow socio-political agendas (i.e. ‘cohesion’ or ‘inclusion’ policies), or are put in place to merely appease ‘customers’ – for example, in airports, shopping centres or universities.

Whether the multi-faith space at Surrey Canal will lead to greater inter-faith dialogue and understanding is an open question. But it will be interesting to see the architectural form that’s produced and what it inspires even if, as Marc Glaudemans notes above, it’s naïve to believe that architecture can serve in any direct way to catalyze intercultural engagement and understanding.

The seminar’s closing session featured comments, to which I’m incapable of doing complete justice, from our gracious local host Marcello Balbo of the Università IUAV di Venezia. Among other things Marcello drew an interesting distinction between “owned” space and “belonged” space. Owned space is a lightning rod for affirmations of ethnic identity; it is contested space. Alternatively, belonged space is flexible, equitable space that best serves intercultural place-making. This resonates with Leonie Sandercock’s framing of the 21st century challenge to planning in the “ethno-culturally diverse city” that, in many ways, concisely sums up the Venice conversation:

“The 21st century project is…a long-term process of building new communities and of actively constructing new ways of living together, new forms of social and spatial belonging, during which fears and anxieties cannot be dismissed but need to be worked through.”

Leave a Reply