Honoring an Archaeology of Tactical Urbanism

In a previous post on this blog I described a bit of our archaeological research at the Ludlow “Tent City,” a 1913-1914 coal miner’s strike camp of 200 tents and about 1200 people in southeastern Colorado. The relevance of this work to the topic of intercultural urbanism was established in the following way:

…there was no apparent ethnic segregation of families within the colony… Based on the stratigraphic positioning of artifacts within cellars dug beneath the tents it appears that colony residents attempted to forge solidarity through the everyday use of certain shared items of material culture. For example, use of plainware ceramics seems to have been preferred over finely decorated Victorian teawares, as the latter would have signaled different social statuses and/or social-climbing ambitions. In other words, strikers sought in their daily practices to emphasize a shared working class identity.

In addition to the evidence apparently suggesting that different ethnic groups were living cheek-by-jowl, “tactical urbanism” is also evidenced by the fact that

…tents were arranged to maximize security and impede surveillance of the interior by passers-by, especially coal company officials and professional strikebreakers. A concerted effort was made to present a “civilized” face to the outside world as a way to combat early 20th century racist stereotypes about immigrants as unclean, ignorant, and naturally violent. The tent city as portrayed in historical documents and photographs evince concerns for health, cleanliness, family, community, and civic order.

Materially, these concerns were reflected by formal street signage, tent numbering, and prominent display of the medical and community tents. Spatially organizing the community with both external and internal factors in mind—i.e., attending to both security and sociability—contributed to a surprisingly long-lived and effective strike.

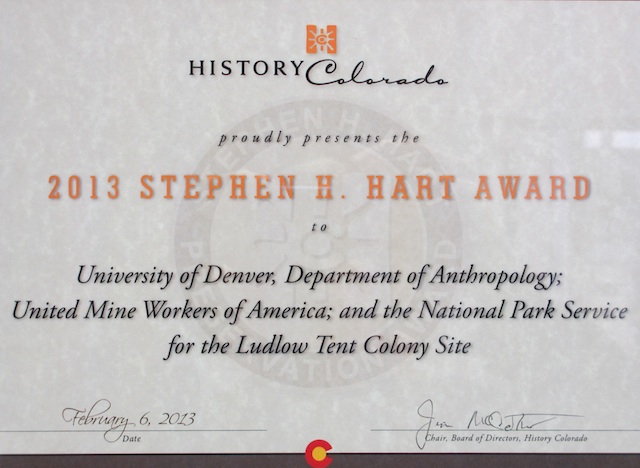

The archaeological work at Ludlow helped win National Historic Landmark status for the site. The icing on that particular cake came last week when History Colorado bestowed a Stephen H. Hart Award for Historic Preservation on the University of Denver’s Department of Anthropology and our partners the National Park Service and the United Mine Workers of America. Here’s an excerpt from the award program text:

History Colorado is proud to honor the Department of Anthropology at the University of Denver for their efforts at the Ludlow Tent Colony site in southern Colorado. During the late 1800s, the Denver and Rio Grande Railroad wanted a local steel source for their growing narrow gauge railroad system. By 1892, their various subsidiaries merged to form the Colorado Fuel and Iron Corporation, known as CF&I. Throughout most of the 20th century, CF&I was Colorado’s largest employer and the center of various labor and management disputes.

One of the most notorious incidents occurred at a tent colony occupied by striking workers, approximately 20 miles north of Trinidad, near the town of Ludlow. Tensions between labor and CF&I led to a prolonged strike in 1913 and 1914. On April 20, 1914, two women and eleven children died in a tent cellar when Colorado militia, battling with striking miners, set fire to the tent. Including the eight miners who were killed, the tragic events of the day resulted in 19 deaths. The Colorado Coal Field Wars are considered to be one of the most important events in American labor history. It is estimated that almost 70 people lost their lives in the Coal Field Wars.

The Ludlow Tent Colony Site was studied by archaeologists from 1997 to 2002…Between 1997 and 2005, the State Historical Fund awarded eight grants totaling almost $850,000 to the University of Denver’s Department of Anthropology to survey, test, excavate, analyze artifacts, and create interpretive displays and materials. The project yielded a wealth of knowledge about the physical nature of the site as well as what camp life was like during the strike… On January 16, 2009, the Ludlow Tent Colony Site was designated a National Historic Landmark by the National Park Service. Much of the information used to argue for the site’s national significance was gained from the archaeological investigations.

Although the settlement tactics employed at Ludlow are not the kind that would draw immediate interest from contemporary urbanists, they’re something that scholars dedicated to a comparative archaeology of urbanism (e.g., here) might find relevant. So too might contemporary tactical urbanists having an interest in building the inclusive city. To reprise the money quote from an earlier post about archaeology’s relevance to intercultural city-building:

… archaeology tells us that at least a few ancient cities were very successful in harnessing diversity’s advantages. Today…we can use little tactics of habitat to accomplish the same goals. Housing can be designed in ways that better integrate marginalized and disenfranchised groups into community. Preserved historic buildings can be turned into low-income housing instead of upscale lofts. The hated (at least within New Urbanist planning circles) surface parking lot can be strategically located to help promote and sustain informal urban economies that, more often than not, have a minority ethnic flavor. We can recognize and defend an aesthetic right to the city. We can better democratize access to public space, markets and other spaces of day-to-day exchange. A variety of strategies for reclaiming urban space can be found within Tactical and Everyday urbanism. Other spatial tactics and strategies for harnessing diversity’s advantages likely await discovery in the ancient [and, we might add, recent historical] urban world.

The partners in the work at Ludlow are of course gratified by the Hart Award honor, albeit for different reasons. NPS can be gratified by the fact that their excellent work in spearheading the NHL nomination has added a rare “shadowed ground” to America’s commemorative landscape. The UMWA can be gratified that federal and state recognition has finally been given to one of trade unionism’s most hallowed and sacred grounds. I’m personally gratified that historical archaeology—up until recently a pursuit that was considered little more than a “handmaiden” to written history—made a critical difference in establishing the Ludlow Colony’s national significance. This helps enhance archaeology’s potential to contribute to other areas of human endeavor—like, say, city-building. Today’s intercultural city theorists, community activists, and tactical urbanists might take note of that.

Leave a Reply