Urban Culture and the Intangible Heritage of Place: ‘Graffiti’ Removal and Preservation

ANARCHETIQUETTE: The removal and preservation of wall writings on public buildings before they are covered up or the buildings themselves are demolished or renovated; efforts to conserve an intangible heritage that would otherwise be eliminated.

Since at least the 1970s the nature of urban graffiti has, from time to time and depending on context, been actively debated. Is it vandalism or artistic expression? Last July The New York Times ran a story reporting that graffiti is on the upsurge in American cities large and small. In Los Angeles, for example, the amount of graffiti removed from city structures was up 8.2% compared to 2010, amounting to 35.4 million square feet. The primary message of The Times story is that the current upsurge in graffiti and the cost of its removal is putting a strain on city budgets. Why this has become a problem is unclear, but factors include anxiety and alienation stemming from the economic recession as well as the “glamorization” of graffiti in some areas of popular culture (for example, this exhibition at the LA Museum of Contemporary Art).

At the same time, the Occupy Movement has reignited interest in public space and the rights of citizens to use it to engage with the affairs of community. In this respect Peter Marcuse has noted a “deficit in the provision and management of public space” and issued a challenged to city leaders and planners to provide spaces that can “fulfill the functions of the traditional agora, places where free men and women can meet, debate, speak to and listen to each other, learn from each other, confront issues of public concern and facilitate their resolution.” To this end, there is nothing in principle that would prevent cities from providing communication facilities, sanitary facilities, sound systems, connections to power lines, protection from elements, provision of food and water, and other considerations to people wishing to use public space in the interests of democratic governance. In short, Marcuse argues that cities need a “Public Spaces Plan” to go along with other established plans for governing transportation, environment, recreation, and various social services. A Public Spaces Plan might also provide—as others have suggested over the years—ample, socially-accessible space to accommodate the kinds of silent, continuous democratic expression and communication that’s represented by graffiti.

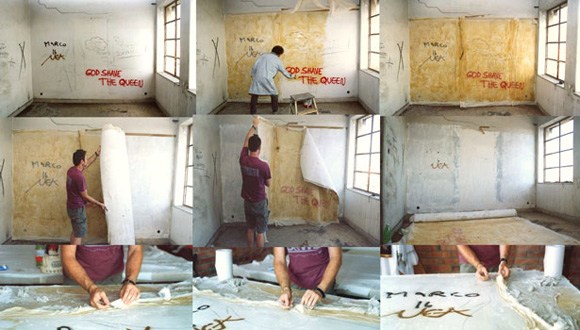

That kind of dedicated civic planning is likely some way off, but in the meantime it’s good to know that there are people doing things right now to not only preserve graffiti and the redemptive democratic messages that often lay therein, but also facilitate their removal. Italian artist Daniele Pario Perra is one of them. Since 2006 he’s been conducting workshops in cities throughout Europe to share a technique called “Fresco Removal.” In this technique gauze containing a natural glue is laid over a frescoed surface to absorb a few millimeters of the substrate containing a message. The message is then transferred to a canvas, and preserved for posterity. Perra is of course unable to deal with “tagging” or the large scale graffiti that focused the Times story. Rather, he’s focused on the smaller traces of “spontaneous communication” that speak to specific local issues in a community; i.e., messages that, in Perra’s words, comprise the “cultural DNA” of a given place. The overriding purpose is to preserve the memories of the city, the “testimonies of an intangible heritage” that would otherwise be lost.

Thanks to the work of my DU colleagues Christina Kreps and Roberta Waldbaum and several sponsoring organizations Daniele Pario Perra brought his work to Denver last spring. An exhibition at Denver’s Museum of Contemporary Art introduced an American audience to Perra’s work, and workshops trained local students in his technique of fresco removal. Just this past week Christina and Roberta participated in the final exhibition of the Anarchetiquette Fresco Removal project at the Sala Borsa in Bologna, Italy. The message of a seminar associated with the exhibition dovetailed with those being sounded by others invested in preserving the city as a site of democratic expression and resistance; namely, that built public space must be made safer for spontaneous communication and creativity. The exhibition in Bologna ends today, but more details about the Anarchetiquette project are available at anarchetiquette.org.

Leave a Reply