Evolution’s City

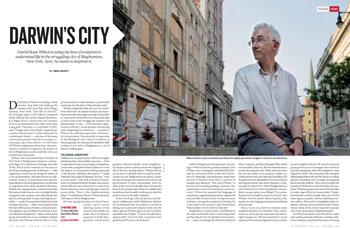

The June 9 issue of the journal Nature (volume 474:146-149) has an interesting article about the work that evolutionary biologist David Sloan Wilson is doing in Binghamton NY to improve life in that blighted city (the home of Binghamton University, Wilson’s employer). Among other things, Wilson is collaborating with town planners and local citizens to bring evolutionary concepts of altruism and “prosociality” to bear on the design of urban playgrounds, parks, and gardens in hopes that this will enhance social interaction, community cohesion, and civic pride.

The June 9 issue of the journal Nature (volume 474:146-149) has an interesting article about the work that evolutionary biologist David Sloan Wilson is doing in Binghamton NY to improve life in that blighted city (the home of Binghamton University, Wilson’s employer). Among other things, Wilson is collaborating with town planners and local citizens to bring evolutionary concepts of altruism and “prosociality” to bear on the design of urban playgrounds, parks, and gardens in hopes that this will enhance social interaction, community cohesion, and civic pride.

This effort raises at least two questions: (1) whether evolutionary scientists should be involved in thus kind of work and (2) how they should go about doing it. Some colleagues, including one quoted in the Nature piece, believe that Wilson has abandoned biology for “a sort of evolutionary social sciences.” One Nature commenter expresses skepticism about what evolutionary theory can add to our understanding of urban problems by alluding to the limitations of the theory as applied to social phenomena.

Another Nature commenter, however, appreciates both the immediacy of the problem and the potential of new kinds of interdisciplinary work to address it. In the words of Will Smith:

All across our country cities and towns are dying and even neighborhoods within cities are dying. Wilson is trying to use his considerable skills to figure out why and how to reverse these declines. So what if it is not pure biology. It is definitely using a lot of his knowledge of biological systems in application to what is probably a hybrid science. Today, in most of science and engineering cross-discipline efforts are where breakthroughs are occurring. Wilson’s efforts should be applauded by his scientific peers, not disparaged because he is “too close” to the work. Yes, others may want to carefully weed through his results to make sure that any scientific conclusions are not skewed by proximity to the subject matter, but progress in this highly complex area of human behavior will not be made by standing around in the ivory tower and looking out the window. Wilson needs all the encouragement that he can get because the problems facing our society are pulling down buildings faster than we can build them. The ivory towers may be next.

This call for greater engagement of academics with their communities, which Wilson exemplifies, is commendable. But accepting that evolutionary theory is relevant to solving urbanism’s problems still leaves the second question of how to use it in this context. Other evolutionists like Steven Pinker and Nikos Salingaros have shown a bit of the way. They both urge that we break with modernist approaches to urban design and architecture and play off of our “default” psychological predispositions as evolved primates. In their view evolved human nature has much to do with the kinds of spaces we are inclined to embrace and, by extension, the quality of the relationships we create with other users of those spaces. Trees, natural light, water, ornamentation, tradition, and building at a human scale all emerge as important qualities in such an approach to urban design.

Wilson appreciates this, but human evolved psychology can’t be the only consideration. Culture and history are also important “contingent” factors. On this count, the work of Setha Low and her Public Space Research Group is relevant. They’ve done the empirical  work on city parks and distilled a number of lessons for planners of urban public spaces. While these spaces must be physically and economically accessible and safe, their amenities (e.g., furniture, facilities, cultural diversions) have to be designed with cultural variation in mind given that different classes and ethnic groups can use the same unit of space differently. Spatial adequacy and flexibility are crucial if diverse urban populations are to be drawn to public space for everyday activities, festivals, and other special events. In some instances, green space may be less desirable than hard space (e.g., open plazas) as a venue for social gatherings. In other words, the green city is not necessarily the most livable city, nor the best route for building the intercultural city. Careful thought must also be given to the kinds of commemorative monuments that define public space given that the histories of user populations also differ.

work on city parks and distilled a number of lessons for planners of urban public spaces. While these spaces must be physically and economically accessible and safe, their amenities (e.g., furniture, facilities, cultural diversions) have to be designed with cultural variation in mind given that different classes and ethnic groups can use the same unit of space differently. Spatial adequacy and flexibility are crucial if diverse urban populations are to be drawn to public space for everyday activities, festivals, and other special events. In some instances, green space may be less desirable than hard space (e.g., open plazas) as a venue for social gatherings. In other words, the green city is not necessarily the most livable city, nor the best route for building the intercultural city. Careful thought must also be given to the kinds of commemorative monuments that define public space given that the histories of user populations also differ.

These challenges notwithstanding, there’s every reason to think that an interdisciplinary or, in the words of another evolutionist named Wilson, “consilient” planning approach integrating evolved psychology and cultural history can provide a useful guide for renewing America’s struggling cities.

Leave a Reply