The Monumental MLK

Public monuments are an important aspect of the good city. In his Art of Building Cities (1889)—a book that helped to establish the modern study of urban design—Camillo Sitte suggested that monuments “bring back historical memories” and constitute “the glory and pride of each city.” Monuments educate residents and visitors and provide spaces to reflect on a shared history. They help create and sustain civic identity by psychologically binding citizens to a place and a past. And, as Sitte was especially insightful in noting, decisions about how monuments are placed within urban space (e.g., within squares and plazas) can significantly expand or sharply limit opportunities to engage in social discourse.

This is why a favorite part of my on-campus and study abroad courses, for instructor and students alike, is our visit to a city’s monumental precinct; e.g., Denver’s Civic Center Park (a classic City Beautiful set piece) and London’s Hyde Park Corner. We study the styles—classical, figurative, abstract, etc.—that characterize different periods of monument building. We ask why these styles change over time. We analyze the placement of, and spatial relationships between monuments. We inquire into what monuments say about cultural values generally: about who, what, and how we remember. We talk about what’s left out or systematically avoided in the realm of public memory and how such omissions might be addressed: whether with a monument, a museum, or some other cultural production.

The mother lode of American civic art, of course, is the National Mall in Washington DC. Last week the final monument to be built on a Mall that was declared closed in 2003—the Martin Luther King Memorial—was dedicated. The monument has inspired much debate and controversy. Some of the reviews have been pretty critical, like Edward Rothstein’s in The New York Times and this piece in The Economist. Debate has focused on the identity of the monument’s sculptor (a Chinese artist rather than an American one), the color of the stone (pale pink rather than black), the physical representation of King (a 30 foot colossus with folded arms, stern look, and missing feet that, arguably, make the subject look more like a socialist autocrat than someone who marched with, and among, the disenfranchised and oppressed), and the King quotes chosen for the Memorial’s wall of inscriptions (nothing about racial division in America or the iconic “I have a Dream”). A major inscription on the south face of the primary King sculpture asserting “I was a drum major for justice, peace, and righteousness” (see photo above) has drawn particular fire for paraphrasing what King actually said in a sermon in Atlanta on February 4, 1968: “…if you want to say I was a drum major, say that I was a drum major for justice. Say that I was a drum major for peace. I was a drum major for righteousness. And all of the other shallow things will not matter.” The poet Maya Angelou notes that the condensation of King’s actual words and elimination of the all important “If” clause contradicts the essence of his Atlanta speech, which is about the evils of self-promotion. She also suggests–famously–that the paraphrase makes Dr. King sound like “an arrogant twit.”

Citizens writing to newspapers and blogs have also offered many good takes. One of the more interesting appeared on the Discussion Forum Archinect:

Does anyone else see the amazing irony in this? All of the other white guys on the National Mall all have buildings, enterable habitable spaces, that house their memories. Whereas MLK is cast aside, outside in the elements, left to fend for his own without the comfort of a white-stone time machine to eternally preserve his image. Which mirrors society perfectly at this moment considering the growing number of homeless, the increasing cost of housing and how housing prices disproportionately affect Blacks, Hispanics and the poor. I guess, judging by our own National Mall, rich white men get roofs whereas black men sleep in the park.

This interpretation overlooks the fact that Franklin Roosevelt’s memorial is also located in an open air landscape on the Mall. But why let complicating facts get in the way of a good story?

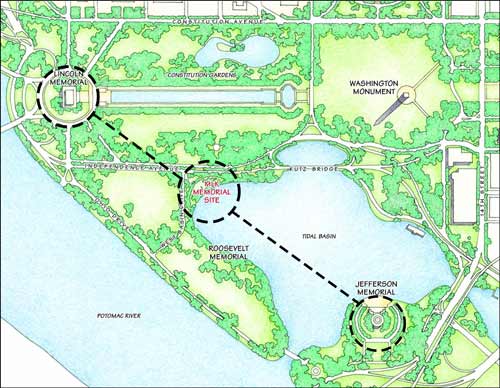

Several pundits have offered some particularly thoughtful analyses. Charles Krauthammer appreciates the monument’s “artistic deficiencies” but suggests that these are trumped by its placement on the last available piece of prime Mall real estate. King might not be in a temple, but he’s centrally located on a “Line of Leadership” that runs between Lincoln and Jefferson. President Bill Clinton noted the symbolic appropriateness of this context and spatial alignment at the monument’s 2006 groundbreaking: “It belongs here…Jefferson told us we were all created equal and Lincoln abolished slavery, but both left much undone.” And that’s why, for this reviewer, King should look stern gazing, as he does, straight across the Tidal Basin at the slave-owning Jefferson. Richard Lacayo, in Time Magazine, reminds us that another thing the monument gets right is its siting in a grove of cherry trees that blossom in April, the month of King’s assassination. Krauthammer, again, notes that for all the debate about what’s included and excluded on the King Wall of Quotes, the totality is consistent with America’s homage to words rather than images of conquest and glory, as befits a nation that was founded on an idea. Clarence Page, among others, notes that the many quotes referencing “peoples everywhere”, “every nation”, and “mankind as a whole” gives we Americans—as well as international visitors to our Mall—a taste of the universalist King rhetoric that has inspired freedom struggles around the world.

For many the simple fact of the King monument’s existence—the only Mall memorial that’s dedicated to an African-American, and a non-President—stamps it as a success. Another indicator of the monument’s success is the debates it has inspired, as sampled above. Public monuments will always embody contradictions, ironies, and omissions. People will always experience and interpret them differently…especially when their subjects are deeply controversial. But history also tells us that heated debate about the form and meaning of a monument can give way, over time, to popular acceptance and even deep affection. Exhibit A is Maya Lin’s Vietnam Veteran’s Memorial. Ferociously controversial at its creation, the VVM has become the most visited and, arguably, best loved of all National Mall monuments. Interestingly, it is frequently mentioned by critics of the King Memorial as an example of how a National Memorial should be designed. But it would be a dull commemorative landscape indeed if all we had to visit were Lin knock-offs, or what several writers (e.g., here and here) have described as “therapeutic” monuments. At the end of the day Clarence Page offers the best advice to MLK monument opinionators: give the memorial a chance. “Fine memorials can be like fine wines. They get better with age. The real test of the King Memorial, as with the others, is how well they look to us in the future.”

Leave a Reply