Dystopian Denver: Are We Protecting the Character of Our City?

Guest Post by Loryn Fujinami

Loryn Fujinami is an emerging Anthropology and Urban Studies professional, who aspires to use an anthropological lens on current issues, with a focus on the relationship between culture and materiality.

It’s not news that things have been changing rapidly in Denver, especially over the last decade. Traffic has gone from bad to really bad. Traditional neighborhoods have sprouted kombucha bars and imported cheese shops. People have started going to Casa Bonita not for the pure enjoyment of mariachi bands and cliff divers, but to re-enact the South Park episode featuring it.

In response to these developments, Denver is implementing large projects in order to accommodate population growth while attempting to maintain the city’s diversity and character. As reported by Planetizen writer James Brasuell, “the City of Denver is making progress on its Denveright planning process—a four-part, multi-year planning process that sets a citywide vision for the quickly growing city”. According to the official City of Denver website publicity, “Denveright is a community-driven planning process that challenges you to shape how we want to evolve in four key areas: land use, mobility, parks, and recreational resources.”

Denver natives display varying levels of resentment for the recent in-migration. While it’s hard to deny the value of improved public transit, new pedestrian and bike trails, and parkland, the resulting deficit of affordable housing, spatial segregation and displacement, and other trappings of gentrification have created significant stress (the recent Ink-Coffee incident being a prime example of growing tensions).

The Denveright Fact Sheet defines the Land Use portion of the plan in terms of “Neighborhood character, function and connections. Ensuring growth and stability in the right places to enhance the livability and sustainability of our communities.” The emphasis has largely been on multi-modal streets and mixed-use development that has allowed for “complete” neighborhoods, or neighborhoods in which people can live, work, shop, and play, like Stapleton and Belmar. Quality-of-life infrastructure is important, but is Denver doing enough to mitigate the negative social consequences of growth?

Take Sloan’s Lake, for example. Developers found an affordable niche and are stuffing it full of one-sized fits all, rectangular, space-efficient townhomes that fill up entire blocks of the old neighborhood. Margaret Jackson’s Westword article about Denver development describes this architecture as, “uninspiring new structures that don’t respect their surroundings.” You can practically see the identically dressed children standing outside of each door, glassy eyes staring into space while they each bounce a basketball in perfect synchronization.

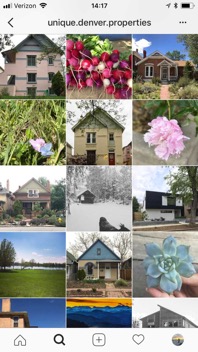

Furthermore, one can barely differentiate one house from another because they are designed to look so similar, except for the odd red railing or blue door. It’s almost like the architect was saying, “Yes, I know these all look exactly the same and no one will ever be able to differentiate them, so we painted the railing red.” This might appeal to a well-heeled young professional or family new to the city and in search of modern living. But it doesn’t make sense to many long-time Denverites, who grew up in neighborhoods where the brick houses were a hundred years old and possessed of varying designs, details, and colors that complimented one another and the area. There are entire Instagram accounts with thousands of followers (@unique.denver.properties) dedicated to traditional Denver-style buildings that make Denver, Denver. The sterile building plans starting to dominate certain neighborhoods are not only an attack on low-income and affordable housing, they are a threat to the very character that makes Denver an interesting and meaningful place to live. This is not a uniquely local issue; it is happening in cities across the nation.

To demonstrate the need for culturally considerate design, I invite you picture any office environment that was built to be standard, clean, efficient, and nothing more. On every desk and in every office you will find plants, books, photos of family, kids, and friends, tissues, shirtless firefighter calendars, awards, and decorations. Everything we know about cities—including those of the ancient world–demonstrates that humans have always used the built environment to create a meaningful existence for themselves. It is contrary to human nature to do otherwise. This is why home decorating, parks, and public art are valued and why dystopian scenarios like the grey, uniform, one illustrated in Lois Lowry’s The Giver are terrifying. Humans make places with character because we have character, and an environment that fulfills this need is the most livable for all kinds of people (not just the minimalists and grey-scale devotees).

To demonstrate the need for culturally considerate design, I invite you picture any office environment that was built to be standard, clean, efficient, and nothing more. On every desk and in every office you will find plants, books, photos of family, kids, and friends, tissues, shirtless firefighter calendars, awards, and decorations. Everything we know about cities—including those of the ancient world–demonstrates that humans have always used the built environment to create a meaningful existence for themselves. It is contrary to human nature to do otherwise. This is why home decorating, parks, and public art are valued and why dystopian scenarios like the grey, uniform, one illustrated in Lois Lowry’s The Giver are terrifying. Humans make places with character because we have character, and an environment that fulfills this need is the most livable for all kinds of people (not just the minimalists and grey-scale devotees).

Salience is a characteristic of the built environment that arouses perception and pleasure. It is a crucial aspect of the famous ethnic neighborhoods found in many U.S. cities, like Chinatowns and Little Italys. It can also be found in the materiality of even the most deprived of places, like Japanese Internment Camps and Native American Reservations. But cultural salience is not necessarily about race and ethnicity, it is about community and making urban places that celebrate and foster culture, not ignore and squelch it.

So, while the official publicity of Denver Planning says, “Diversity, affordability and good urban design/architecture are key to complete neighborhoods as well,” it is an after-thought that has not been articulated in concrete plans. The “as well” makes it clear that it is not leading the planning thought process but trailing behind. Speaking as a local, this is not enough.

For urban planners to firmly grasp what cultural salience means in the built environment, we need to learn a lot more about it. This is why anthropological studies of how humans interact within a cross-cultural and archaeological urban built space context are so important, as livability is closely connected to the human experience of place.

Luckily, the City has recently completed a set of community discussions, the Blueprint Denver Workshops, where people can voice what “complete neighborhoods” mean to them. Until local feedback can refine the city plans, we can hope that projects, like the Sun Valley Revitalization Project, heed the input of the community already present there and avoid exclusive change and the pricing out of long-time Denver citizens.

The essential question to ask is not only how do we accommodate growth but also how do we protect the character and integrity of this historic city so that it will still be a meaningful place for all of the inhabitants? Change is inevitable, but our response needs to be culturally considerate, inclusive, and just. The last thing we need is a bunch of lost professionals wandering the streets at night searching for their unit in a sea of cookie-cutter townhomes, cursing themselves for one-too-many drafts at the new neighborhood microbrewery and wondering why they hadn’t moved somewhere with a good design-review committee.

Leave a Reply