The Evolution of Green Urbanism

The evolution of urban planning has been the subject of several recent museum exhibitions, blog posts, books, and infographics. These representations of planning history are useful for several reasons. They remind us of where we are and how we got here. They stimulate debate about the people and ideas chosen for inclusion as well as exclusion. Finally, they promote critical discussion of contemporary planning values, principles, and ambitions. This in turn offers some possibilities for rethinking how planners and architects practice their craft.

The Singapore-based Center for Urban Greenery and Ecology recently published a paper of mine in their journal CITY GREEN called “Planning Sustainability: The Evolution of Green Urbanism.” What follows is a summary of the paper. Unlike other formulations of planning history, mine is archaeological and cross-cultural, casting widely across time and space. Nine significant episodes in green planning history are described. These episodes cover the time frame of 5,000 years ago to the present, and geographical areas that span the globe.

A caveat before proceeding. Picking big moments in planning history is an inherently subjective exercise. There are many people and ideas to choose from. I’ve chosen people and ideas that had, for better or worse, a physical impact on cities and more-or-less broad appeal. I present my selected episodes chronologically, but I use the term “evolution” loosely. Each episode has a specific historical context. The nine episodes do not build upon each other in ways that reflect a simple linear trajectory leading from primitive to advanced, or simple to complex. I close with a consideration of the relevance of this historical and cross-cultural knowledge for dealing with the challenges of 21st century city-building.

1. Original Urbanism: Mohenjo-daro

My history starts pretty close to the beginning of urban life with the Indus Valley (Pakistan and western India) cities of 2300 BC. A distinct and original “cradle of civilization,” Indus Valley societies implemented sophisticated infrastructural innovations in water management that served sanitation and human health. The city of Mohenjo-daro in Pakistan is an exemplar. Nearly all houses contained bathing facilities, and streets incorporated numerous wells and drains. The latter moved waste out of the city via brick-lined channels. Water management also figured in the architecture of social integration. Mohenjo-daro’s central Citadel—an acropolis of fired brick—featured a “Great Bath” that likely played a role in public cleansing rituals. Thus, it’s reasonable to regard Mohenjo-daro as our earliest example of the “Eco-City.” Certainly, its system of water management is as historically significant as the 19th century infrastructural improvements made in Paris under Baron Georges-Eugène Haussmann (more below) or in London under Joseph Bazalgette.

Excavated ruins of Mohenjo-daro, with the Great Bath in the foreground. (Wikimedia Commons/Saqib Qayyum)

2. Old Urbanism: Sennacherib’s Nineveh

Urbanization occurred in Mesopotamia even earlier than the Indus Valley, beginning with Uruk at 3600 BC. However, it’s only with much later cities governed by named rulers that we see concerted investments in urban planning. The most compelling example is Nineveh under the reign of Sennacherib, 704-681 BC. Sennacherib’s experimentation with innovative technical solutions to urban problems made him a pioneering urbanist. He widened Nineveh’s public squares and straightened its streets to bring in more light. He developed sophisticated engineering works that channeled water to the city from mountains 80 kilometers away via canals and aqueducts. Innovative water screws brought water to higher levels, creating “Hanging Gardens”: trees suspended on terraces that were built up around a central pond. These gardens have long been the stuff of legend, historically associated with another famous ancient Mesopotamian city, Babylon. However, Stephanie Dalley makes a compelling case for locating the Hanging Gardens in Nineveh. These gardens almost certainly served functions comparable to today’s “Green Roofs”: filtering dust, absorbing CO2, and reducing heat.

Drawing of a garden at Nineveh, showing aqueduct and a corner of Sennacherib’s palace. (Wikimedia Commons/Public Domain)

3. Eco-Social Urbanism: Jenné-jeno

Africa south of the Sahara has always been a blind spot in global histories of cities and urbanization. Western assumptions about race and the cultural capacity for innovation are partly to blame. The West African (Mali) city of Jenné-jeno, dating to AD 400-800, is particularly instructive as an early example of ecologically and socially conscious urbanism. The Jenné-jeno urban complex consists of several mound-based communities distributed within a four-kilometer radius along the margins of the Niger River. Its population totaled up to 40,000 people. The mound centers appear to have been ethnically distinct but functionally interdependent, guided by principles of specialized craft production and the reciprocal exchange of goods and services within a generalized economy. This made great ecological sense in a dynamic and unpredictable environment characterized by high inter-annual variability in food production. It’s unlikely that Jenné-jeno’s unique “clustered city” model of urban planning, or other interesting African models, can be transferred wholesale to today. But the example retains some relevance for imagining how ecosocial interdependence and innovation might be better developed within contemporary cities. Indeed, we might be seeing reflections of this ethos in the self-organizing qualities of the “informal urbanism” that characterizes today’s mega-cities of the Global South.

4. Baroque Urbanism: Haussmann’s Paris

The Baron Georges-Eugène Haussmann’s renovation of Paris between 1853-1870 was precedent setting for its greening of the medieval cities of Europe. Haussmann used baroque planning principles—straight, tree-lined boulevards, diagonals, squares, parks, and terminating vistas focused on public monuments and civic buildings—to open up the city to air and light. Like his anonymous predecessors at Mohenjo-daro, Haussmann’s public sanitation works—subterranean pipes, sewers, and tunnels—served the cause of improved sanitation, fresh water delivery, and human health. On the other hand, Haussmann’s projects displaced poorer residents to outlying areas and gentrified the urban core. His wide boulevards made it easier for authorities to quell civic unrest by quickly transporting armies to sites of social disturbance. For these reasons among others, Haussmann’s approach to planning earned him great international popularity among urban elites. “Paris Envy” spread among other European capitals, producing similar forms of urban renewal. In the United States, Daniel Burnham re-imagined Chicago as “Paris on the Prairie.” New York’s powerful planning czar Robert Moses studied Haussmann’s work and applied his tactics in ways that both greened and socially segregated the city.

5. Ebenezer Howard’s Garden City

Ebenezer Howard’s Garden City is often cast as the moment when the idea of the Eco-City first appeared. Howard’s proposal was directly stimulated by the pollution, congestion, and social dislocations of the industrial city. Howard sought to reunite people and nature, to hybridize “town and country.” Planning elements featured in his famous concentric ring diagram included a central park, radial roads, single family homes, neighborhoods, zoning for different land uses, vast open space, and a greenbelt. Howard’s model of the Garden City was a powerful influence in the mid-20th century, spawning “New Towns” movements in many countries. His influence soon faded, but made a comeback on the 100th anniversary of the original Garden City formulation through the work of Peter Hall and Colin Ward. Hall and Ward’s updating of Howard re-imagined cities that could that fulfill the Garden City’s original aim to house a diverse, mixed income, and self-sufficient citizenry. Despite an admirable green sensibility, the Garden City concept remains an inducement to urban sprawl and in practice has trouble meeting its social diversity goals.

6. Le Corbusier’s Radiant City

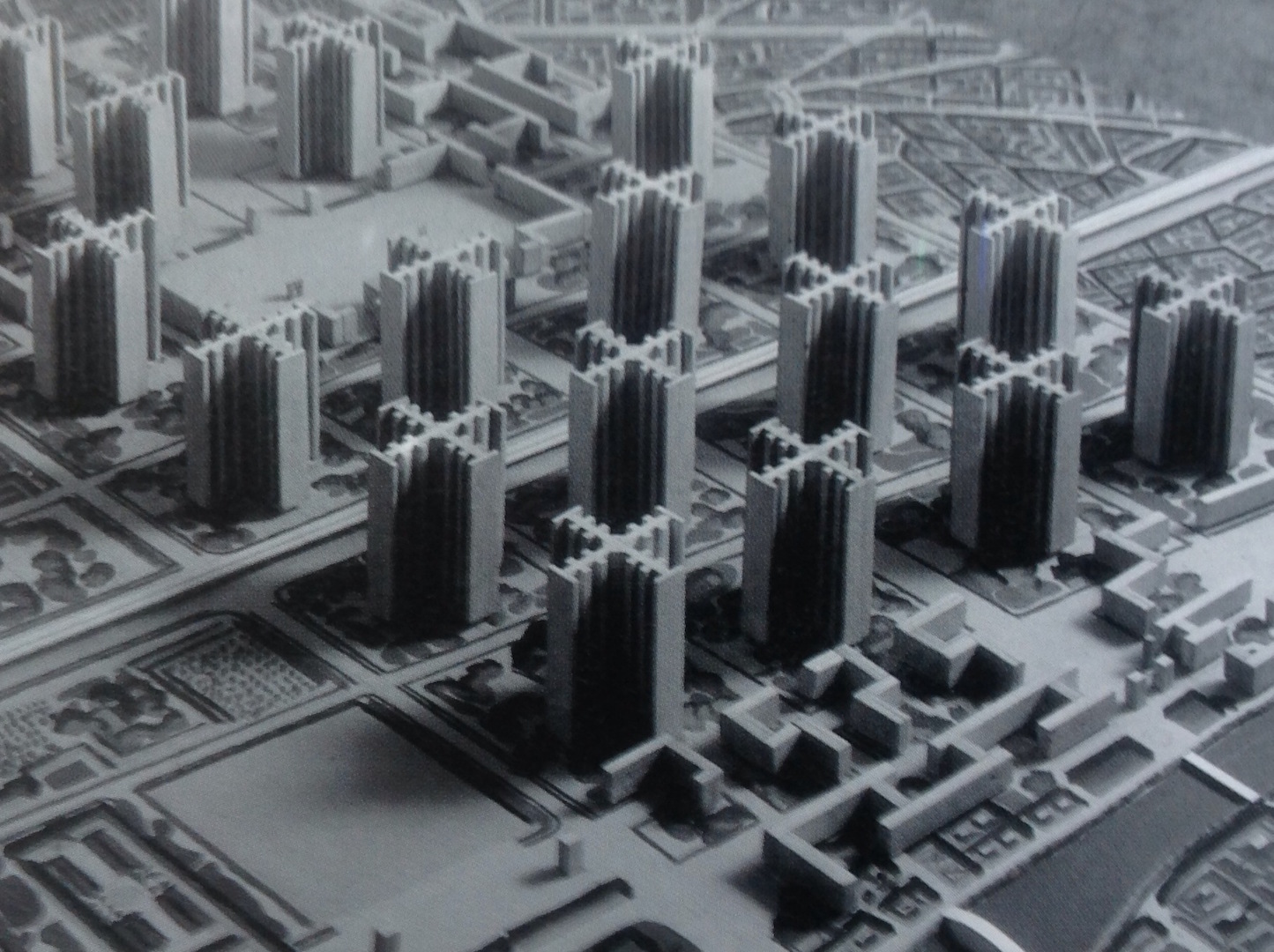

The Swiss architect Charles-Édouard Jeanneret, aka Le Corbusier, drew on the traditions of Haussmann and Howard to originate what we know as “modern” urban planning in the late 1920s and 1930s. Like Haussmann, Le Corbusier proposed opening up the city by eliminating streets in favor of broad arterial roads and increasing parks and open space. Channeling Ebenezer Howard, he imagined an encircling band of Garden Cities on the urban periphery. His city center would be vertical, distinguished by superblocks containing tall, glass-and-steel towers in green settings. The entire city was conceptualized as one immense park. “Towers in the Park” would serve as “radiant prisms.” The Radiant City’s crowds would live in peace and pure air, where, in Le Corbusier’s words, “noise is smothered under the foliage of green trees.” The influence of Le Corbusier was considerable in the renewal of American cities in the last half of the 20th century. However, the overall effect was not quite as intended. Towers in the Park tended to frame desolate, windswept, and alienating spaces. Diverse neighborhoods gave way to expressways and residential segregation by race and class. Still, the Radiant City concept continues to have resonance today. The approach is mirrored in the planning of eco-cities in China and elsewhere, e.g., Tianjin Eco-City.

Le Corbusier’s model of the Plan Voisin for the reconstruction of Paris. (Wikimedia Commons/SiefkinDr)

7. Frank Lloyd Wright’s Broadacre City

Like Le Corbusier, the American architect Frank Lloyd Wright was inspired by Howard’s Garden City. But Wright radically decentered it. Instead of building up, he proposed building out, expanding across the landscape. Broadacre City grew out of the landscape, with an organic architecture that expressed the local environment and responded to the local climate. Wright’s famous “Usonian” houses employed native materials, natural light, and passive solar heating. Broadacre City got lots of exposure in the American popular press during the 1930s. It had special appeal because it comported with an American ideology of rugged individualism and an emerging motor car culture that pulled citizens ever outward in search of prosperity. Clearly, suburban sprawl is part of Broadacre’s legacy. We’ve also seen a proliferation of the building types associated with Broadacre: low, horizontal ranch houses, mobile homes, roadside markets, drive-through restaurants, and suburban malls. These abundant artifacts of Broadacre continue to bedevil urban planners seeking a genuinely green and sustainable urbanism.

8. North American New Urbanism

New Urbanism and its progeny—Smart Growth, Transit-Oriented Development—emerged in the 1990s to reintroduce traditional town planning in the United States, using both Garden City and Broadacre City principles. New Urbanism broke with Broadacre in calling for clear town centers and edges. But it argues, with Wright, that architecture and landscape design should grow from local history, climate, and building practices. The Charter of the New Urbanism urges compact, mixed use centers, walkability, human-scaled buildings, tree-lined streets, and adequate green space. Its ecological approach seeks to harmonize neighborhood and region. Andres Duany’s urban transect is New Urbanism’s signature image. New Urbanism has been a commercial success in the United States, but critiques abound. It can be reasonably argued that New Urbanism repackages the basic principles of Old Urbanism as exemplified by cities like Nineveh. It hasn’t always remedied automobile use or served the cause of walkability. And while New Urbanism is committed to green principles, it hasn’t been effective in accommodating ethnic or income diversity or reducing socio-economic segregation in American cities.

9. South American Social Urbanism

My last episode is perhaps the most relevant one for guiding efforts going forward. It draws on the Global South and is exemplified by the cities of Curitiba, Bogota, and Medellín. Here, charismatic mayors drove targeted, experimental interventions in the urban fabric that served both the environment and society. In Curitiba, Jaime Lerner created parkland to control local flooding, planted millions of trees, and recycled just about everything. His Bus Rapid Transit system, with its stylish stations, de-stigmatized bus travel so that more people would use public transportation. Enrique Peñalosa did the same for Bogota, pairing his Transmilenio bus system with one of the most extensive networks of bicycle lanes in the world. In Medellín, Sergio Fajardo built iconic libraries in parks and expanded the Metro cable car system to connect the poorest areas of the city to the urban core. All three mayors exemplify experimental urbanism in the tradition of Sennacherib. But Social Urbanism has not been an unalloyed success. Bus systems can be overcrowded, car traffic and congestion are still present, people have been displaced, and gaps between rich and poor remain. But the principles and strategies of Social Urbanism still have promise: replacing the “big plans” of Haussmann, Burnham, and Le Corbusier with small urban projects, and using “urban acupuncture” to produce interventions in the built environment that might catalyze larger social effects.

Conclusion and Prospectus

My framing of the Green City’s evolution doesn’t directly address today’s developing “Eco-urbanism” movement. But it’s evident from this brief history that Eco or Green Urbanism has ancient, cross-cultural roots. Infrastructural development at Mohenjo-daro presages what we see in 19th century Paris and London. Sennacherib anticipates Haussmann, Le Corbusier, and the South American mayors who implemented strategies and methods of Social Urbanism. Jenné-jeno’s leaders, located off the radar of traditional urban studies, integrated ecological and social concerns into a single, distinctive brand of urbanism. Today’s New Urbanism largely replicates what we see in Old Urbanism. Of the better-known people in my history, Ebenezer Howard is being revived, Le Corbusier is still being channeled, and Frank Lloyd Wright continues to cast a long shadow over the art of building organically.

Thus, there are significant lessons from the past that might inform today’s green, sustainable planning. The past is a deep repository of reference points for considering the do’s and don’ts of contemporary urbanism. For me, the primary challenge for 21st century Green Urbanism is to better connect environmental and social justice goals; to unite the sustainability conversation with the equity conversation. This is a disconnect in many current versions of Eco-urbanism. In so doing we should rethink the urban governance models that can bring us to an effective integration. We might be guided by the wisdom of the civic leaders throughout history who exercised enlightened, top-down activism while simultaneously supporting bottom-up initiatives for change.

One Comment

Leave a Reply