The Towers of London

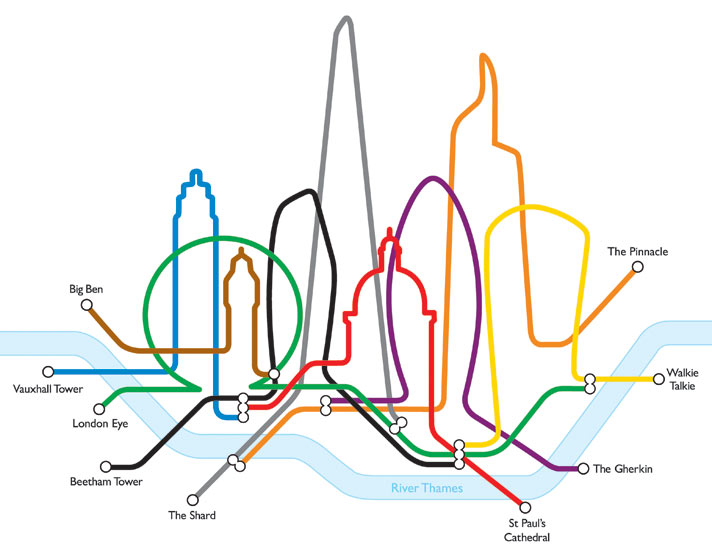

LONDON 4 January 2013. London is currently experiencing a relative frenzy of high rise building. The existing and proposed structures are known locally by their shapes, including “The Shard,” “The Cheesegrater,” and “The Walkie-Talkie” (or—better in my view—“The Pint”). Just over a month ago The Observer’s architecture critic Rowan Moore examined this building trend. He posed a series of excellent questions that should be asked of all towers proposed for any city on earth:

Do they… show consideration of scale or proportion or try to make a meaningful relationship with their surroundings? Is there anything special about their detail? Is there consistency or integrity in their overall concept? Do they create handsome new public spaces at their base? Does their internal planning produce the best possible living or working spaces, which are well laid out and make good use of daylight? Failing all the above, do they have any worth in the rapidly debasing currency of iconicity? Are they, in other words, exhilarating to contemplate or innovative—do they transmit some sort of buzzy excitement about London being a dynamic world city?

Regrettably, Moore has to answer “no” to all of these questions when they’re asked of the Towers of London. He argues that most of the two dozen or so towers currently being built in the city are of poor architectural quality. They’re located in places that don’t make sense, where they either interfere with the “long views” of historic sites, or they’re not well served by public transport. They don’t create appealing and accessible public spaces, either at their bases or in the form of viewing galleries on their upper floors. Perhaps most importantly, they’re non-compliant with master planning principles or are being built over the objections of local neighbors and statutory authorities.

Mr. Moore is not an anti-tower Luddite. He notes that towers can be beautiful, and that a good part of London’s genius over the last 2000 years has been its ability to accommodate changing architectural styles. But for Moore today’s towers are “mostly units of speculation stacked high, garnished with developers’ ego…There is no vision, concept or thought as to what their total effect might be on London, except that it will be great.”

I was impressed by the number of reader comments on Moore’s piece—404 submitted over the course of two days. These surely cover the waterfront of popular opinion about high rise building in London. It’s a very close call as to which position wins out: pro-tower or anti-tower. Many readers agree with Moore that London’s Towers are another form of urban blight. This comment, from “redshrink,” is typical:

Their gimmicky shapes and their scale conceal a dull sameness at their core. Their apparent variety is only a thin veneer on the model of a streamlined, corporate city that ends up looking like any other of a similar mold—like Shanghai or Dubai.

Tower haters often propose more aggressive central oversight and planning to keep greedy developers in check and prevent the London skyline from being completely destroyed. Other readers suggest that London’s skyline can’t be destroyed because it never really had one, although admirers of Christopher Wren’s churches and Canaletto’s representations of them would surely disagree. One reader suggested that the absence of skyline is falsified by anyone who’s been to Parliament Hill, or even to Primrose Hill. Those who see the towers as enhancing the skyline suggest that a city has to change with the times. As Moore notes, this adaptability is a big part of London’s distinctiveness and appeal. London is not a set museum piece like Paris, whose well-preserved urban core is beautiful but also borne of autocracy rather than liberty.

The most thought-provoking reader comments introduced a more nuanced and complicated calculus for evaluating the pros and cons of tall buildings. One reader (David Kane) suggests that London towers must be evaluated in light of the city’s differentia specifica as an urban phenomenon:

I agree with the comment that Paris has been well served by town planning, as have many other cities. However, it’s a little late to impose top-town town planning on London. It has never been such a city. London is a series of villages that have, over time, become part of London. London’s intrigue is in its infinite variety, not its beautiful cityscape. I like The Shard, because I like the mix of old and new, but I confess, I’m not convinced by all the new buildings going up and some of them may look out of place. None-the-less I prefer to see London in a state of flux, adapting to the needs and demands of its people.

Another reader (“280E”) plays off of Moore’s reminder of London planning officer Peter Rees’ belief—apparently ignored in practice—that towers work best when clustered together:

By avoiding the creation of a concentration of tall buildings (so far anyway), the problem of architectural quality is exacerbated, since every building needs to carry the full responsibility of the skyline by itself. If you look at cities famous for their skylines, such as NY or Chicago, most of the buildings are actually quite uninteresting individually (particularly in NY’s case), but they add up to a great overall effect, and can be very engaging at street level.

A third reader (“Petengeth”) likewise suggests that towers are best appreciated not on their own but rather in relationship to something else, specifically the older buildings with which they coexist. Such coexistence doesn’t have to be uneasy. In fact the modern and the ancient can bring out the best in each other:

I don’t live in London, but visit occasionally. One of my favourite things is that contrast between shiny glass towers and tiny ancient pubs squeezed in in little gaps, like reminders of the past. Something London does really well. Save the best and build the best, that is the answer.

The “best” towers, then, are (1) conscious of their historical context, (2) cluster together and make collective meaning with their fellow travelers, and (3) invite contrasts (or comparison) to what has come before. By this accounting London’s towers do pretty well (but for a different assessment, see here). The Cheesegrater does slope in order to accommodate the view of St Paul’s Cathedral from Fleet Street (regrettably, The Shard ruins the view of St. Paul’s from Hampstead Heath). The Pint does symbolize something widely associated with British culture, the building’s accumulationist logic (i.e., its more valuable upper-floor bulge) notwithstanding. And as many others have observed, The Shard does recall a Wren spire, especially when viewed from, say, Hackney. But in another sense these buildings still suffer from a lack of intercultural resonance. What would a 21st century tower look like that turns on an intercultural sensibility, rather than individual architectural conceit?

Leave a Reply