Europe’s Mean Streets

One of the delights of being in Bologna recently was meeting, courtesy of my colleague Gabriele Manella, other scholars doing urban research in the University of Bologna’s Sociology Department. I’m honored for our anthropology department here at DU to be an Associated Partner for grant proposals that have been submitted by these UNIBO colleagues to their country’s Ministry of Education for research on urban sprawl and sustainable growth. While in Bologna I learned about some other work that UNIBO sociologists are doing on the uses of public space. One project is a detailed study of Bologna’s Piazza Giuseppe Verdi, a public square that symbolizes the relationship between the city and its university and that’s famous for the diversity of its local user population (e.g., see here). Another is a study of the material strategies—in the form of new urban furniture—being used by civic officials to exclude the homeless from the use of public space.

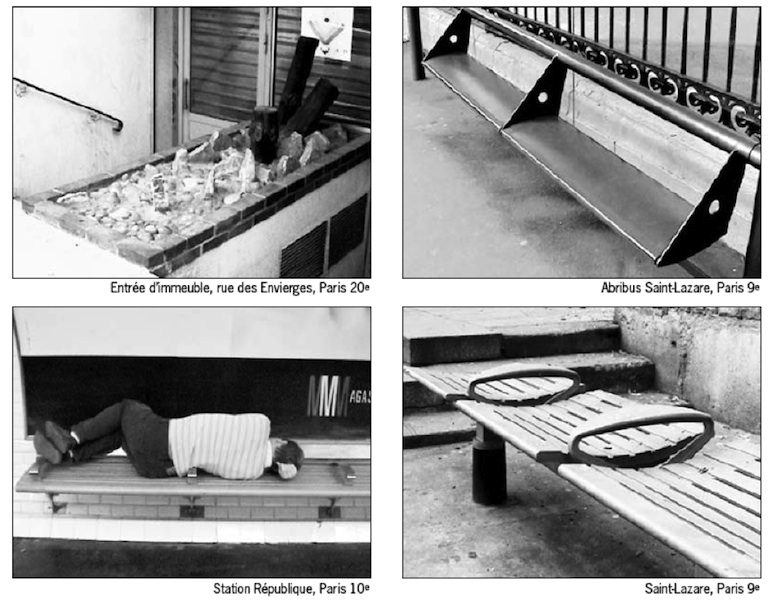

It’s the latter theme that focuses this post. I first encountered these homeless exclusion strategies—the “bum-proof” bench, the fortified dumpster, the gated civic building—in Mike Davis’ classic study of Los Angeles. They are now the stuff of frequent commentary in the blogosphere (e.g., here, here, and here). A 2006 report by the European Observatory on Homelessness details some of the subtle and not-so-subtle ways that architecture and street furniture—and their far-from-innocent decorative elements—are being used to control the lifeways of people who are homeless in Europe. According to this report “anti-homeless” benches, gates and fences have been spreading all over the continent.

Parisian Banc Publics (From G. Paté, Sociologique sur l’ordinaire des Espaces Urbains, Actes de la Recherche en Sciences Sociales 159, 116-120, 2005)

UNIBO colleagues Marco Castrignano and Maurizio Bergamaschi presented a very interesting and richly illustrated paper about the Italian context called “The Street Furniture Law: How Homeless Can Be Excluded from Public Space” at the 2010 meeting of the International Visual Sociology Association held in Bologna. Castrignano and Bergamaschi note that in the last several years 800 local ordinances on the safety and management of public space have been implemented in some 400 Italian municipalities. These ordinances are designed to combat the “illegal occupation of public space” and maintain the “decorum” of the city. The use of particular kinds of street furniture figures prominently as way to enforce this urban decorum. In some instances (Treviso, Trieste, Padua) public benches have been completely removed from city streets. In others (Verona, Bologna, Savona) they’ve been replaced by forms having intentionally anti-homeless designs; e.g., barrel-shaped benches or conventional ones with bars that prevent lying down. The new furniture has been placed in parks, squares, and streets with heavy pedestrian traffic.

Some anti-loitering interventions recently observed in Bologna are akin to the anti-roosting spikes used to keep pigeons from perching on window ledges:

And then there are tactics such as these that likewise keep people off of ledges and out of doorways:

Castrignano and Bergamaschi note that anti-homeless street furniture very often goes unnoticed by the average Italian citizen. The foreign traveler is even more likely to miss it given the many seductive and distracting charms of “Old Urbanism.” The material tactics of habitat that socially-divide and exclude are a revelation for my American students once they know to look for them. Economic downturns and insurgent movements for social change are likely to produce increasingly sadistic street environments in Europe, the United States, and elsewhere (e.g., Japan) until we figure out ways to better mesh the need for urban decorum with the right to the city.

Leave a Reply