Saving Arapahoe Acres

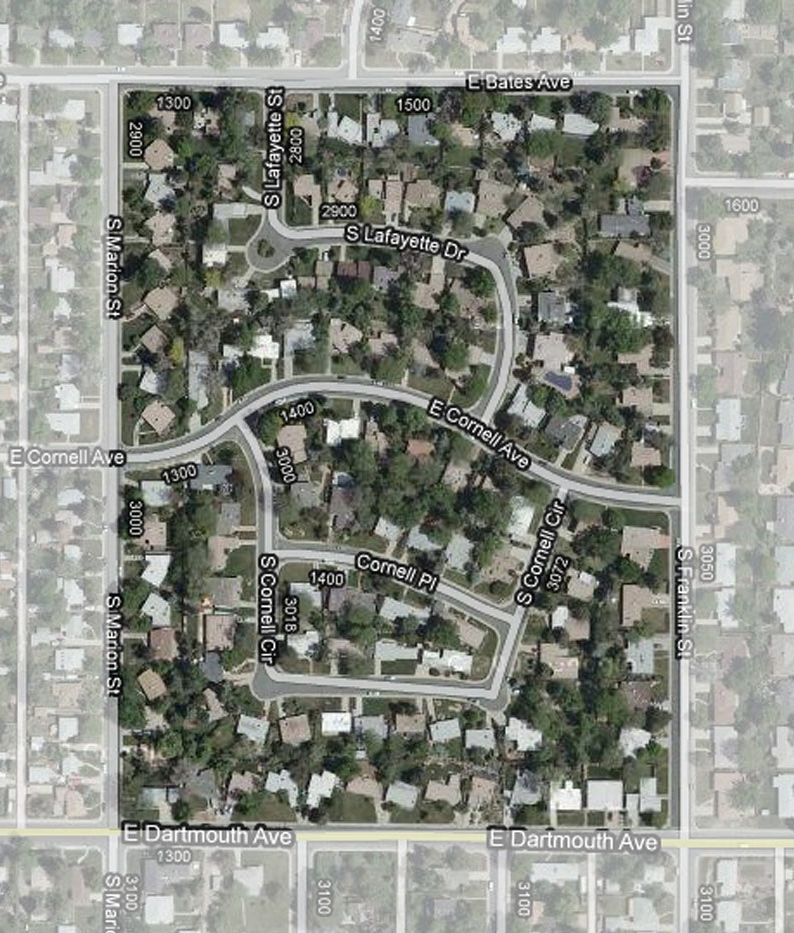

Arapahoe Acres is a nationally famous suburban subdivision located just south of the University of Denver in Englewood. It was built between 1949-1957 by the developer Edward Hawkins, with help from the architect Eugene Sternberg. Sternberg was then employed by the University’s regrettably short-lived (1946-52) School of Architecture and Planning. Hawkins was inspired by Frank Lloyd Wright’s Usonian architecture and Sternberg by the Bauhaus International style. Their collaboration produced a unique neighborhood that, in 1998, became the first post-World War II residential subdivision in America to be listed on the National Register of Historic Places. The best history of the neighborhood has been written by Diane Wray, who also spearheaded the Register nomination. In May 2011 the Denver magazine 5280 cited Arapahoe Acres as one of best places to live in Denver. The subdivision has just been named by This Old House magazine as one of the “Best Old House Neighborhoods 2012.”

Arapahoe Acres is a nationally famous suburban subdivision located just south of the University of Denver in Englewood. It was built between 1949-1957 by the developer Edward Hawkins, with help from the architect Eugene Sternberg. Sternberg was then employed by the University’s regrettably short-lived (1946-52) School of Architecture and Planning. Hawkins was inspired by Frank Lloyd Wright’s Usonian architecture and Sternberg by the Bauhaus International style. Their collaboration produced a unique neighborhood that, in 1998, became the first post-World War II residential subdivision in America to be listed on the National Register of Historic Places. The best history of the neighborhood has been written by Diane Wray, who also spearheaded the Register nomination. In May 2011 the Denver magazine 5280 cited Arapahoe Acres as one of best places to live in Denver. The subdivision has just been named by This Old House magazine as one of the “Best Old House Neighborhoods 2012.”

Because of this recent publicity a story about Arapahoe Acres was a featured last week on the front page of The Denver Post. The story described a growing tension in Arapahoe Acres as new homebuyers renovate their homes in ways that threaten architectural coherence and uniqueness. This raises the question: Has the collision between old and new brought this neighborhood to a tipping point?

Denver landscape architect Eric Crotty, Arapahoe Acres resident since 2002, was quoted at some length in The Post story. Crotty previously detailed his concerns about “unsympathetic renovations” in Arapahoe Acres in a 2011 online piece for the Cultural Landscape Foundation. The Foundation had identified Arapahoe Acres as one of America’s “At Risk Landscapes.” There, Crotty provided this money quote about the subdivision’s historical significance:

The neighborhood represents a snapshot in time and records the exuberance of the post-WWII era for experimentation and enthusiasm for distinctive residential architecture in a prosperous country.

Crotty admits that today the homes are “comparatively inefficient in many ways” and that renovation and maintenance are necessary. In other words, he understands that change is inevitable. But he also worries that Hawkins’ and Sternberg’s “original design intent” is being compromised by even the most well-meaning renovations. They are taking a cumulative toll and threatening the one thing that best guarantees the value of each individual homeowner’s investment: the overall architectural coherence of the neighborhood’s design aesthetic. The Cultural Landscape Foundation piece ends with Crotty calling for a re-establishment of covenants that Hawkins had originally devised but that hadn’t been enforced since at least 1967 (when Hawkins left the neighborhood), including provision for an “Architectural Control Committee.” He suggests re-establishing such a committee to help residents balance the values of preservation and sustainability. The Post story ends with Crotty making another plea, this time for broader education about the neighborhood’s distinctiveness:

We have to teach people what makes this place special…My interest is less now on how we get immediate neighbors to understand it but how do we create pressure from the outside on residents…It’s about creating a dialogue [with] the larger design and preservation community that filters into the neighborhood.

Reader comments on Denver Post stories are always interesting for what they suggest about the pulse of public sentiment on an issue. In this instance more than a few readers were put off by Crotty’s passion for historic preservation and, I suspect, his call for creating outside pressure on residents. The majority of 25 commentators reduce the Arapahoe Acres issue to one that pits property rights and personal freedom against historic preservation and top-down imposition of regulations. By my count reader sentiment runs about two to one in favor of property rights, with the very first commentator predictably opining that “The neighborhood NAZI’S [sic] should mind their own business or move to UTAH [emphasis in original]. Such “property rights at all cost” comments—again, predictably—suggest a deep ignorance of Denver’s architectural history and completely miss Crotty’s point that it’s the wider public’s appreciation of Arapahoe Acres as an iconic place on the American landscape that makes the neighborhood desirable and that adds value to the investment of those who live there. You’d think that individual Arapahoe Acres homebuyers—who can undoubtedly afford to live in many other Denver neighborhoods—would want to take this wider sentiment into account when considering their investment and the factors that can protect or erode it.

I use Arapahoe Acres in my classroom teaching at DU because the neighborhood has considerable pedagogical value in illustrating not only Mid-Century Modern housing but also the residential component of Wright’s imagined Broadacre City and the more general concept of the city as “a work of art.” So, I appreciated Crotty’s point about educating residents and would-be residents about the neighborhood’s historical significance. In working with Arapahoe Acres I’ve drawn on the really nice website by Tom Lundin that pairs photos of individual houses with lovely sketches detailing their exterior features. Students are always surprised that such a neighborhood exists a stone’s throw from campus and I know that some seek it out to have a closer look. Those who do agree that it’s a “really cool” neighborhood, as resident David Steers opined in The Denver Post.

Academics should be under no illusion that they’re strategically positioned to exert meaningful pressure on people to think and act in particular ways. But we can always hope. It would certainly be tragic for both residents and the wider, admiring public if Arapahoe Acres was renovated beyond recognition. Charles Birnbaum, president of the Cultural Landscape Foundation, makes great sense where he tells The Post that “there’s a lot of wiggle room” to renovate and update individual houses in ways that simultaneously preserve the neighborhood’s exterior coherence. The wiggle room allows for the wholesale gutting of interiors to meet the changing needs of American families, and I doubt that Hawkins, Sternberg, or Frank Lloyd Wright himself would object to solar panels on the peaked and cantilevered roofs. Minimally, the question of Arapahoe Acres’ future doesn’t have to be framed as an “either/or” as regards property rights and historic preservation. It will indeed be worth watching how, as one Post commentator describes it, the “interesting social dynamic playing out in this little area” will evolve in the months and years ahead.

Leave a Reply