Educating for Urban Sustainability…And Remembering Doug Darden

The Chronicle of Higher Education, to which I’m a long-time subscriber, channeled its inner urbanist last week with three city-related articles in the January 27 edition.

Scott Carlson wrote about “America’s Health Threat: Poor Urban Design.” He featured the work of Richard J. Jackson, former head of the National Center for Environmental Health at the Centers for Disease Control. In print and on public television Dr. Jackson has alerted citizens and policy-makers to how the American built environment is making us fat and killing us–literally. Dr. Jackson’s prescription going forward is to build for better social connectivity and in ways that encourage physical activity. New Urbanism is mentioned as one viable approach for filling this prescription.

Nigel Thrift, Vice-Chancellor of the University of Warwick in England, contributed an opinion piece called “The Pull of Cities.” He suggests that we need a sea change in the way we think about cities now that over half the world’s population lives in them. Dr. Thrift sees cities as “increasingly both networked and perforated by information technology in ways which are bringing them together as actual forceful entities rather than as simply conglomerations.” He urges us to “grow a distinctive urban science” oriented around information technology that reunites the technological and the social. This will involve changing the university’s curriculum to better integrate the natural sciences with the social sciences and arts and humanities, and perhaps changing the university itself.

Finally, Jon Christensen, Robert McDonald, and Carrie Denning build upon the education theme by calling for an “Ecological Urbanism for the 21st Century.” The key takeaway message is to do more integrative, interdisciplinary work, as Dr. Thrift suggests. Minimally, there’s a need to integrate urban planning with ecology and conservation science. But there’s also a need to go beyond. Margaret O’Mara, co-organizer of the “Now Urbanism” seminar at the University of Washington, suggests that both urbanists and scientists “pay too little attention to politics, economics, and history” in designing cities. I’d add that they also pay too little attention to culture. Attending to all of these variables is critical if urbanists are to better root their dreams and plans for re-making neighborhoods in what O’Mara describes as “what is already there.”

The last time The Chronicle prominently featured architectural design and training in such a way was with a long article by Sarah Williams Goldhagen nearly 10 years ago called “Our Degraded Public Realm: The Multiple Failures of Architecture Education” (but see also this piece by David Orr). Goldhagen hit some of the same notes about form, context, and curriculum as Thrift and Christensen et al., including this key money quote:

What do graduate programs in urban design, and especially in architecture, teach? Although they vary from institution to institution, certain commonalities exist. One is that such programs generally give short shrift to the study of sociology of urban and suburban life, leaving students without the knowledge or tools to understand the environments for which they design. As a result, students tend to focus their ideas overwhelmingly on forms, with little informed awareness of how their buildings will contribute to a larger urban composition and to the social existence of communities.

While Goldhagen called for more training in the pragmatic aspects of design, she also implicated the need for more interdisciplinary work. It’s interesting that her recent piece in The New York Times linking architectural form to the visual metaphor of the tree as shelter walks that talk. Goldhagen calls for an engagement between design disciplines and the revolution in cognitive neuroscience; that is, for re-conceptualizing the built environment around the fundamental workings of the human mind. I suspect that Nigel Thrift would approve.

I’ve had my own brush with the issues at stake in these various essays. In 1994 I gained some experience jurying student architectural projects at the University of Colorado-Denver’s College of Architecture and Planning. The design studio was taught by a Special Lecturer in Architecture and Fellow of the American Academy in Rome named Douglas Darden. Doug died prematurely from leukemia in 1996, at age 44. At the time Doug was known to be a very creative thinker and inspiring teacher. I met Doug through my girlfriend Martha Rooney (now Martha Rooney-Saitta) who had taken a studio with him. Doug—open-minded thinker that he was—thought it would be interesting to have an anthropologist on the jury in order to balance, complement or—perhaps ideally—contradict the opinions of the practicing architects and professors of architecture.

The jury I sat on was for a project that Doug called “Ghosts.” I regret that I can’t remember the specific design challenge that Doug set for his students, but the students produced work ranging from a neo-modernist development that riffed on an Ancient Pueblo Indian theme (which pleased me greatly given that my academic reputation, in an earlier life, was gained as a North American archaeologist) to a modernist high rise with a huge, retractable mechanical claw that emerged from its middle stories. I remember interpreting the latter as a philosophical critique of the modernist project—an observation that escaped the professionals on the jury but that the student designer confirmed was his primary intention. In fact, in this student’s view the anthropologist was the only juror who “got it.”

Jurying was great fun and also confirmed that anthropologists (and other students of culture) can make distinctive contributions to the design professions. Nonetheless, I came away with the distinct impression that for students and professionals alike architecture was– as Goldhagen would note nearly 10 years later and Thrift nearly 10 years after that– largely about technical form and not so much about social context; that it was largely perceived as a technical challenge rather than a social opportunity. That experience has always stayed with me and continues to be the touchstone against which I evaluate proposals for remaking the human built environment.

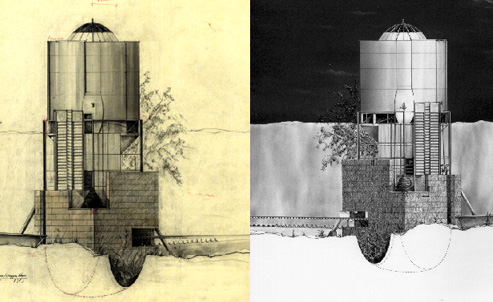

After reading the Chronicle articles I googled Douglas Darden. I was happy to find a 1998 article by Jean LaMarche in Utopian Studies called “The Life and Work of Douglas Darden: A Brief Encomium.” The article focuses on the contents of Doug’s 1993 book Condemned Building: An Architect’s Pre-Text. The book contains 10 imaginary projects dealing in “unfulfilled desire” as well as death (Doug’s own was not far off), which perhaps explains the “Ghost” theme of the studio that I juried. The most critically acclaimed project in the book is Oxygen House. This is a house designed for a person Darden calls Burnden Abraham (based on a character in Faulkner’s As I Lay Dying), an invalid who needed to be housed in an oxygen tent. Like his students Darden sought to interrogate the modernist project, in this instance turning modernism on its head by casting architecture not as “machine for living” but as a “machine for dying.” In so doing Doug provides a useful counterpoint to the kind of designs for urban health championed by Dr. Jackson.

LaMarche’s characterizations of Doug’s work (three of which I excerpt below) helped me better understand why I liked Doug and found his studio so energizing. And, more importantly, why I believe that good urbanism should incorporate an architecture of possibility that’s informed by culture, history, mortality, and the many other dimensions of human social life. LaMarche writes:

[for Darden] architecture is fundamentally connected to all other human endeavors, all other forms of cultural production. Thus, all human undertakings can be explored as part of it and architecture, in turn, can be examined to shed light on these as well: in all forms of making we reveal some of the most important and at times intransigent questions that humans continue to deliberate. More importantly, we reveal the constant struggle with what is not there and thus, our constant utopian desire or yearning.

And:

Darden had that poetic urge to explore his own demons and, more importantly, to engage in an architecture that did not exclude the other conditions of being human—our fears, our hopes, our dreams, and the necessity for resolve…

And finally:

In the end, Darden extends architecture, makes it larger than it was before him. He does so by demonstrating how architects can successfully draw on a much wider array of artifacts for inspiration and guidance [perhaps like the student who channeled the ancient Pueblo Indians in her final project for “Ghosts”] in the design and production of the material world.

One Comment

Pingback: Goldhagen, from “Degraded Public Realm,” in “Educating for Urban Sustainability” « Civism and Cities