Composing Cosmopolis

As a small army of urbanists and pundits have pointed out, the recent violence in Ferguson and Baltimore reminds us that we haven’t moved very far toward eliminating the social conditions that produce race-based civic unrest. These events have prompted some useful soul-searching about the relationships between urban design, architecture, equity, opportunity, and community—in short, about what a socially just, genuinely cosmopolitan city should be.

Rethinking the design and distribution of public space must be part of the agenda going forward. Public space in American cities shrank or became less accessible in the last half of the 20th century as the nation’s love affair with the automobile deepened, residents fled the urban core for the suburbs, and the city center was overtaken by blight and private interests. Such outward movement was enabled by federal housing and highway legislation that made it both appealing and economically rational for citizens to leave the urban core to claim their bit of the American Dream on the open frontier.

Today we’re experiencing something of a historical reversal. The so-called “Millennial” generation—well educated, tech savvy, and culturally creative—is returning to the city center in search of mixed use live-work environments, upscale amenities, and walkability. At the same time, insurgent movements like 2011’s Occupy Wall Street have highlighted the scarcity of truly open, public spaces in the urban core and the limitations of “POPS”—Privately Owned Public Spaces—for serving the citizen assembly requirements of healthy democracies. The urban demographic is also diversifying and, with that, come different ideas about what a good public space should look like and how it should function in the realm of everyday lived experience.

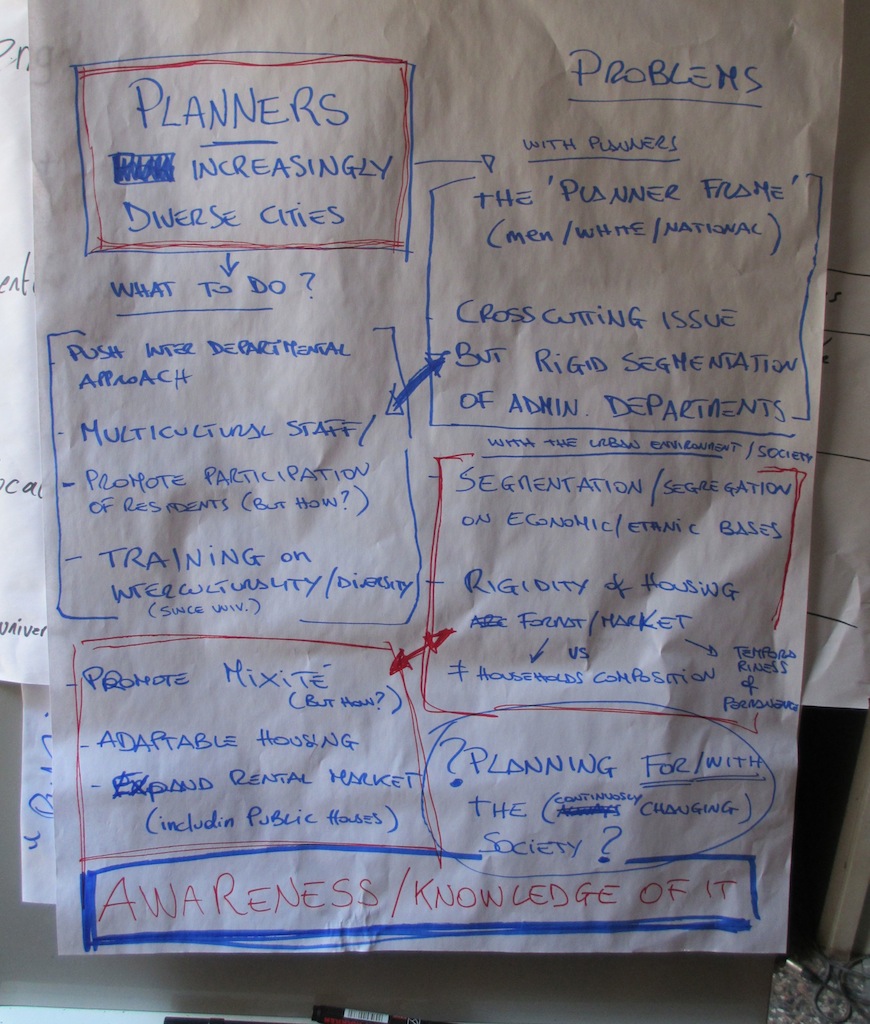

The planning and design professions are scrambling to meet the challenges. Architecture and planning schools do not typically teach about cross-cultural and trans-historical differences in how people value, create, and use public and private space. The community outreach methods employed by professional planners and developers (including the scheduling of meeting times and the techniques employed for soliciting citizen input) are largely geared to accommodate the majority culture. In my experience here in Denver, the so-called “creative class” exerts disproportionate influence on the form and direction of this public dialogue. There’s a well-intentioned commitment among planners and politicians to engage the public, but few seem to understand that there are many publics.

Grass roots planning and place making movements like Tactical Urbanism—an ostensibly revolutionary effort to experiment with temporary, short-term projects that reclaim streets and parking lots for public use—show what’s possible but are still promoted by middle class actors having the time, inclination, and means to experiment. Such experiments don’t significantly challenge the neoliberal approach to urban development (e.g., see here and here). They can easily and unknowingly reproduce what George Lipsitz describes as the “white spatial imaginary,” a worldview steeped in privatism, consumerism, and implicit racial superiority. Tactical urbanism and other forms of experimental placemaking simply can’t address the systemic, structural conditions that produce inequalities in access to the public realm and the differential involvement of cultures and classes in the enterprise of city building.

Thus, it would be wise to search widely across time and space in search of leads for composing cosmopolis. It was at a Council of Europe Intercultural Cities Program placemaking seminar at the Università IUAV di Venezia in 2012 that I met a bunch of people dedicated to this cause. Among them was Noha Nasser, the founder of MELA Social Enterprise. I describe the array of outreach methods Noha used in one of her projects in Birmingham, England, in a longer version of this essay at Planetizen and also elsewhere on this blog. These methods encouraged residents to identify as citizens who have a shared stake in the collective good of the neighborhood rather than as members of a distinctive ethnic group. The process employed in this particular effort was not simply consultation but rather novel engagements in a kind of “citizen-driven master planning.”

Other Venice seminar participants contributed specific design proposals—also discussed at Planetizen and here—inspired by local knowledge and collaboration. One proposal from Stadslab European Urban Design Laboratory offered a redesign of the main city park (Gorky Park) in Melitopol, Ukraine. Melitopol is an Intercultural Cities Program pilot city. It is home to over 100 nationalities. Significantly, the redesign of Gorky Park as an intercultural public space was based only on the cultural values that its designers took to be commonly shared by all of the people who cohabit Melitopol. These shared values are found—to invoke a wonderful descriptive phrase from participating architect Beatriz Ramo—in the “magnificent rituals of the simple.” These rituals include celebration (apropos for Melitopol given the number and variety of feast days celebrated by the city’s residents), love (given that the city is known for the large number of wedding shops to be found on its streets), and sport (given that sport is one phenomenon that brings cultural diversities together world-wide). In Stadslab’s final report design team coordinator Marc Glaudemans nicely captures the rationale at work:

We have no naïve belief in the power of architecture to fundamentally affect people’s values or behavior, but if the basic conditions are there, the architecture of the park can reinforce such behavior and provide an immensely richer environment for being and living together in the city.

Leonie Sandercock, in her books about Cosmopolis and other writings, suggests that the 21st century project of city building is a long-term process of creating new ways of living together, requiring what she calls “new forms of social and spatial belonging.” Martin Luther King, Jr. pitched the same idea—using a very appropriate metaphor—nearly 50 years ago by calling for a “radical restructuring of the architecture of American society.” George Lipsitz re-frames this goal as the transformation of Blacks and Whites into “new kinds of humans…people capable of creating new racial and spatial relations.” David Harvey speaks of “cultural emancipation” and the need to construct “new forms of sociality.” Interestingly, this notion of social and spatial “belonging,” as well as other ideas about collaboration and integration, anchored a summary of the recent New Urbanism Congress in Dallas.

Thus, contemporary urban unrest in Baltimore and elsewhere appears to be producing a certain convergence of thought across disciplines and worldviews about the need to plan and design interculturally. American cities are going to have to embrace such a project if they hope to become more equitable and inclusive. While the more insidious racialized policies of urban renewal, residential zoning, and population distribution are for the most part a thing of the past, class segregation and ethnic containment are occurring by other means. My fellow anthropologist Nilson Ariel Espino nicely explores this ground from a historical and cross-cultural perspective in his new book called Building the Inclusive City: Theory and Practice for Confronting Urban Segregation. We need better ideas for planning and design of the built environment that reflect our shared heritage as members of Homo sapiens and our shared identity as citizens. But we’ll also need to respect ethno-historical differences in the way that people create and “own” public space. Multiple urbanisms—Old, New, and even Ancient—can point us toward useful examples of processes and products for accomplishing this task.

Leave a Reply