Is ‘Sustainable’ Urban Placemaking Elitist?

Jamaal Green thinks so. Playing off of a recent post by Kaid Benfield, he suggests that mainstream sustainability advocates must “move beyond a consumptive conception of cities that’s based on attracting a preferred social elite, whether they be footloose millennials or middle class families.” Too often ignored are current residents who typically have limited options about where to live and can be easily displaced by the force of gentrification as newcomers move in. The benefits of gentrification don’t readily trickle down.

Green’s message is important. There’s still a dearth of voices addressing the “equity deficit” in our thinking about sustainable urbanism. Some other standouts are Richey Piiparinen, who usefully asks of the urban “livability” trend: for whom, and at what cost? Like Green, Piiparinen suggests that the focus falls disproportionately on the coveted group of “cultural creatives” having disposable income. Consequently, current urban interventions—tactical or otherwise—too often reproduce the divide between amenity-rich and amenity-poor neighborhoods. Similarly, Roberto Bedoya detects in creative placemaking practice a blindness to the social and racial injustices at work in society. He challenges placemakers to become more aware of “the politics of belonging and dis-belonging,” noting that “before there is the vibrant street one needs an understanding of the social dynamics of that street.” Neeraj Mehta builds on this theme, asking:

For whom are we trying to create benefit when implementing our creative placemaking strategies?…Which people do we want to gather, visit, and live in vibrant places? Is it just some people? Is it already well-off people? Is it traditionally excluded people? Is it poor people? New people? People of color? ….We need to create an explicit pro-equity agenda to our creative placemaking efforts, be explicit about who benefits from the beginning, put it in our logical models and include it in our measurement.

Julian Agyeman takes up this challenge most comprehensively in his recently published book Just Sustainabilities. Agyeman usefully considers both the physical and symbolic character of the urban built environment. The “complete streets” and “transit oriented development” agendas are rooted in middle class visions, values, and narratives. They can signal something very different to people of color, immigrants, refugees, and other urban underclasses. Newly established bike lanes and pedestrian zones can breed resentment when biking and walking—historically the primary transportation options for low-income people—become fashionable for people of greater means. Their appearance can also increase anxiety because they often portend gentrification and displacement. Other celebrated sustainability initiatives like community gardens and urban farms can remind non-white citizens of the oppression their ancestors experienced under plantation and share-cropping systems, when sometimes all that’s really desired by residents is a simple, affordable grocery store. Even equally accessible urban parks and other public spaces can signal cultural and sub-cultural inclusivity or exclusivity depending on signage, amenities, and whether adequate space is available for different kinds of outdoor activities. Agyeman describes various bottom-up and top-down placemaking initiatives in cities like Boston and Bogota that are more congenial to the needs of urban minorities and underclasses, and exemplify “shared narratives of equity and justice.”

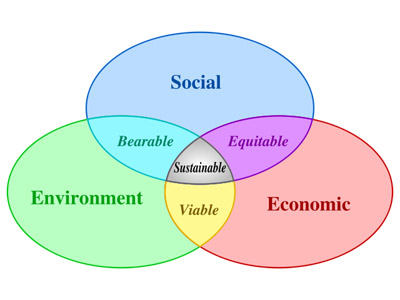

Certainly, there can be some significant overlap between mainstream sustainability agendas and explicit pro-equity agendas. In the Sustainable Cities post that provoked Green’s critique Benfield embraces a broad notion of sustainability that reflects concerns well beyond pollution and resource consumption. He notes that cities must be made to work for all people given a rapidly diversifying urban demographic. Benfield admits that some tactical urban interventions are frivolous and self-indulgent (see also here). He has also written about the dangers posed by commercial gentrification to minority businesses in suburban areas that attract immigrants. He has written positively about the rejuvenated South Lincoln (Mariposa) neighborhood in Denver, and its developer’s use of a “cultural audit” to solicit a broad spectrum of community opinion about desired features and services. The Project for Public Spaces channels both Mehta and Bedoya in articulating the challenges facing inclusive placemaking. The new MIT Department of Urban Studies and Planning report on Places in the Making takes equity concerns to heart where it problematizes the concept of “community” (typically invoked far too casually in most platemaking discourse; for a Denver example see here), urges greater attention to the “right to the city,” and advocates a more “nuanced” understanding of political power and social capital. New Urbanists acknowledge the need to better engage with working class and minority groups.

“La Alma de la Mariposa” Mural by Jeremy Ulibarri (left) and “Mestizaje” sculpture by Emanuel Martinez (right), South Lincoln Neighborhood, Denver (D.Saitta)

Tactical urbanism has its virtues. The Lighter, Quicker, Cheaper (LQC) interventions celebrated by Places in the Making attract attention and spark the imagination. And where imagination is sparked, permanent changes that enhance livability and vibrancy can follow. But not everyone has the time, resources, freedom, or interest to experiment with LQC. The approach is no substitute for a more substantive focus on questions of housing, transportation, and affordability that prioritize social equity and the accommodation of cultural difference. Advancing the equity agenda requires changes to planning theory and practice that, in Agyeman’s terms, are transformative and not simply reformist. In this regard, Bedoya usefully recommends that placemaking practices be informed by critical race theory as well as more conventional spatial planning and economic development theories. Learning from history also helps. Failure to do so risks—as Green notes—reproducing earlier forms of urban renewal that resulted in the marginalization, containment, or displacement of our most vulnerable citizens.

This essay was reposted to Sustainable Cities Collective.

Leave a Reply